Ontology in the Quantum Era: A Retrospective

From an ontological perspective, a term that was coined only in the last century or two to denote a specific branch of philosophy related to being, or reality itself, in deep antiquity our ancestors simply had myth. Various tales and stories that were handed down from generation to generation, that spoke of topics such as the creation of the world and mankind, stories of great valor and love, and destruction stories too no doubt. These myths, these tales or narratives – what we refer to throughout collectively as a people’s mythos, were the means by which ancient man explained the universe and their place in it. One can think of the mythos of the ancients as a map of, or description, of their ontology – in narrative, metaphorical form of course.

The Egyptian, Greek, Babylonian and even Christian creation myths, their cosmogony or creation mythos which provided sometimes fantastic explanations as to how the universe came into existence and in turn how mankind itself was formed, no doubt stemmed from and reflected the socio-political reality of the respective cultures within which these so-called “religious” systems emerged – societies where individuals struggled for access to food and shelter, where the existence of the society itself depended on the seasons and the weather, their river valleys and their periodic flooding, which in turn were guided by the seasons which the ancients knew were related to the stars and the sky. It was this mysterious universal order which the ancients depended upon for survival, and the explanation of how it all began, and what force(s) guided its creation and preserved it, were embedded in, and made up the essence of, their respective mythos and in particular their respective cosmogonies.

All of these environmental factors defied rational explanation to these peoples, and so these ancient peoples created tales, i.e. mythos, that explained these natural and cosmic mysteries, touching on natural phenomena as well as (what we today would call) “spiritual” or “religious” phenomena. Why did the rivers flood some years and not others? Why did the sun rise every day? Why did the herds that the depended on for food and other utilities of day to day living show up some years and be absent others? What happened to the Soul after death? Was there a Soul? It was these questions that plagued the ancients and that formed their perception of their reality, or their world. And their world depended very much on Nature. They lived with Nature and relied on it. This concept of the nurturing and creative force that was inherent to the world around them, Mother Earth as it were, was a core part of their reality upon which their lives depended and their prevailing mythos, and their socio-political structures, reflected these beliefs.

To the ancients, the world around them was best described by principles of interdependence and the cyclical nature of the world around them. The ancients had to plant food, had to procreate, had to hunt for meat. They had their religious festivals and rites which essentially were the praying or asking of the divine, the unknown and unseen anthropomorphic hand(s) that guided these mysterious cyclical processes, cyclical processes which ultimately were governed by the process of life and death itself, and so they developed ritualistic practices to pray to these gods upon whom their survival, and the survival of their peoples and societies, depended.

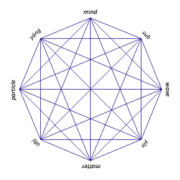

And their metaphysics, the intellectual framework that underpinned their understanding of reality and the world around them, was entirely integrated and coupled with their understanding of the human’s psyche, mind. The psyche of ancient man, as philosophy emerged as societies advanced to form civilizations, and an intellectual framework for the cosmos, and man, evolved, their understanding of mind, was as an independent intellectual construct which guided and shaped individual agents (the psyche), but also as fundamentally and intrinsically connected to, a manifestation of really, Cosmic Mind. This framework evolved mostly as philosophy emerged as the dominant intellectual framework for understanding reality, philosophia supplanting mythos in a very real sense, but nonetheless rooted in mythos, narratives that again explained how the universe came to be, how the gods were created, how mankind was created in their image, and how and why mankind was granted authority and dominion over the Earth. Ultimately, and quite distinctively when compared to more modern understandings of reality, more objective realist and deterministic frameworks, in antiquity the psyche, while looked upon as an independent entity that drove individual behavior and actions, was also fundamentally connected to, a manifestation of, the cosmos and universal order from which their entire worldview was based really. This is the Logos essentially.

Much changed and evolved as (Western) civilization advanced, and philosophia along with it – through antiquity and the Hellenic/Greek and Roman/Latin eras, through the Christian and then Islamic times, up through the Dark Ages, and then perhaps most poignantly through the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution from which emerged much of the rational foundations of the modern era, intellectual foundations that were, and still are to a large degree, perplexed by the findings of Quantum Mechanics, bringing about a new intellectual revolution, i.e. the Quantum Era, which although rested on the same principles of the Enlightenment, i.e. Reason, nonetheless called into question some of the cornerstone principles upon which objective realism and determinism, the byproducts of this Age of Reason, rested. Lost in all of this of course, as almost an unintended consequence, was the connection between mind, and the Cosmos – the death of the Soul as it were, or in stark terms as described by Nietzsche, the death of God himself. While certainly much was gained as Reason supplanted Religion in the West in the last few centuries, nonetheless something was clearly lost as well. The mystery of the connection of the individual with the cosmos became myth really, or at best perhaps simply the domain of Religion, as unscientific a pursuit as there is.

But imbedded in ancient mythos, a core tenet as it were, was the principle that the universe and mankind himself, emerged from some primordial source, this cosmic soup from which gods and men and all living creatures came forth, at the hand of God in the Abrahamic religions and at the hand of some non-anthropomorphic principle in the Eastern philosophical systems which have gained some prominence in modern times as Western religious systems in their orthodoxy and irrationality have been for the most part discarded. The ancients saw themselves as integrated with this primordial substance. They were born from it and they would return to it and it was this eternal truth that governed their relationship to the world at large. This idea of the separation of the “physical” world, and the “spiritual” world had not yet arisen. And how could it? There was nothing in the world around them that would indicate this separation. Even dreams had their own reality in this world, and different states of consciousness were different reflections, or different perceptions, of reality to them. Empirical Science had not yet been established. There was not a “real” world and then a dream/spiritual world. That distinction had not yet been formulated by human kind.

But with the advent of civilization itself, as it spread throughout the Western world, came the rise of Reason, and the Mind and Intellect as the supreme tools of man to understand the universe, the invention as it were of the Ancient Greek philosophers. Society advanced to the point where the individual, or at least the individuals who focused on theological and philosophical matters, did not have their lives and thoughts obsessed and focused on survival. They did not have to pray to the gods for their food and clothing, their sustenance, these came from the inventions of mankind and society as it developed, using reason and logic as their basis, the first technological advances, by the manipulation of the material and physical world and leveraging the human mind in all its creativity and power, establishing the foundations of modern Science, even though they didn’t call it that back then (Aristotle’s practical philosophy). They could spend their time focused on other things, on intellectual matters such as ideal forms of government for example, and on mathematics and astronomy, and other topics which all fell under the broad heading of philosophia. The bedrock of Western civilization had been laid down.

This advancement of thought, which paralleled the advancement of civilization, was only possible because the basics of life were now present without much effort. Their minds could focus on other things. And so was born Reason, which supplanted myth and faith (theology) to a large extent, which was the means by which mankind established agriculture and domesticated animals to do their bidding, through which more advanced societies evolved, forms of government were established, and perhaps most significantly, through which language and writing were invented to support all of these efforts via the evolution of human civilizations accelerated dramatically.

Having said that, and not disparaging the importance and significance of these developments in advancing mankind, if you look at some the hunter-gatherer societies that exist today, societies that very much reflect this very ancient form of existence and dependence upon nature for survival, forms of society that pre-date the evolution of Western civilization for several tens if not hundreds of thousands of years – in the recesses of Alaska, the Amazon basin, Australian outback or central and eastern Africa – you will find the same belief systems of ancient man that reflect a worldview of interconnectedness, a spectrum of reality that includes the earthly material world as well as the spiritual world (theology), where there exists a fundamental reliance, and belief, on the unknown and unknowable creative principle from which the universe was created and which in turn preserves it, across which the cycle of time – the movement of the stars and sky, the passage of day into night, and the passage of life into death, and the notion of illumination or spiritual rebirth – moves into perpetuity. This very ancient belief system, worldview, persists even today in these small pockets, shedding light on how ancient man viewed himself, and how he viewed the world around him and his place in this world.

Philosophy today has evolved to denote that branch of knowledge that studies such abstract concepts as existence, knowledge, values, and mind using reason and logic at its basis, and in some cases even mathematics, as the source of truth. Metaphysics in turn, is that branch of thought that sits between, or atop, Philosophy and Physics and explores such topics as the nature of existence and reality itself, or ontology, a further abstraction and extension of Philosophy in many respects. Metaphysics is distinguished from Physics in the sense that it attempts to explain phenomena that could be considered unreal, or lacking material substance or verifiability by empirical or scientific methods that are associated with Physics proper. Prior to the advent of Science, as marked by its distinguishing characteristics of empiricism and scientific method as a means for elucidating and discerning truth and reality, Science was referred to as Natural Philosophy, and this in fact was the term that was used by Newton as the title of his great work Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

The Eastern philosophical tradition, Vedānta and Buddhism in particular, in antiquity as well as in their modern interpretation, rest less on the supremacy and eternal truths as laid out in their respective scriptures, but more so on the communication, reception, understanding, and ultimate realization of the essence of the teachings as handed down from teacher to student through time immemorial. This was a core tenet of their belief system, and a core principle that was embedded in their teachings, scripture included, from the very beginning. This is why the core philosophical teachings of Vedānta were called the Upanishads, a Sanskrit word which means literally “sitting at the feet of”, implying that the true teachings of the Vedas were meant to be transmitted directly from teacher to student through oral transmission, a form of revelation that is facilitated by the teacher and imparted to the student.

But what makes one belief system more true or “real” than the other? Was it reason? Was it the ability to empirically study and test results based upon a certain idea of measurement that man had created? Was our faith in the mystery of the universe and the hand that guided it so far-fetched and so juxtaposed with Science that it needed to be abandoned entirely? After all of the research and progress, with all the fancy instruments, with sending people to space and the study of the heavens with super powerful telescopes, with even the calculation of the origin of the (known) Universe itself as reflected in Big Bang Theory – after all this, at the very boundaries of Science, we still in some sense struggle today with notions of space and time, and reality itself in a sense, begging the question as to whether or not Science itself, on its own, can explain everything there is to know, everything that we as a thinking species truly want, or even need, to know, or perhaps more fundamentally everything that there is.

Even after thousands of years of scientific development and advancement, where we can effectively communicate with each other beyond the boundaries of time and space across the Earth in a way we never would have thought would have been imaginable, where we have an understanding of how the Universe came into being at a level that the ancients at least perhaps would have never dreamed possible, what we can definitively say at this point – based upon empirical evidence and data, that has been proven over and over again through verifiable and repeatable experiments and is supported by extraordinarily advanced mathematics – is that:

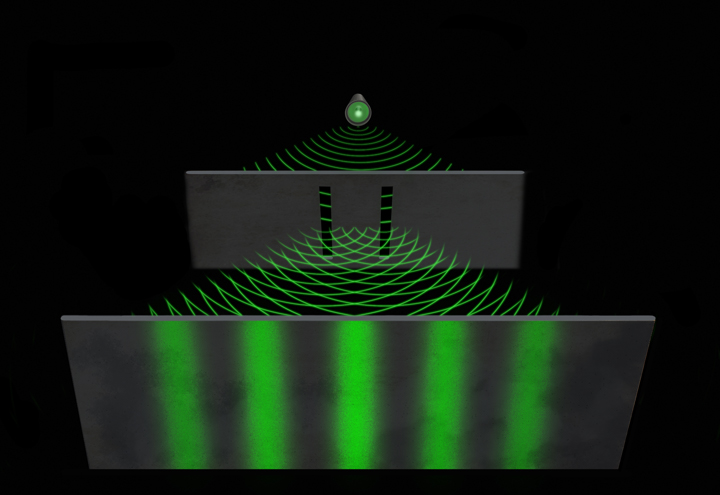

- the underlying substratum of physical reality behaves according to fundamentally non-local principles that are inconsistent with Classical Mechanics: the nature of subatomic reality is non-local in the sense that the location and momentum of subatomic “things”, i.e. corpuscles, must take into account, and in fact appears to take into account, it’s entire environment – i.e. the so-called “system”.

- that matter and energy are fundamentally equivalent and can be converted into each other: at the subatomic level and even macroscopic level, matter and energy exhibited the same properties, and you could formulate theories upon this behavior, which could be “verified” via experiment. That in fact energy and mass are mathematically equivalent, related by the (assumed constant and fixed) speed of light.

- that even in Classical Mechanics the principle of Relativity is required in order to provide coherence and consistency at the cosmic scale: that at the other end of the spectrum, our classical notions of space and time and three-dimensional space must be abandoned in order for Classical Mechanics to be consistent and accurate when viewing the universe at the grand scale, i.e. the cosmos.

What we are left with is the fact that Newtonian Mechanics in fact is only an approximation of the behavior of “objects” and “things” when considered at the human scale, and different models must be used to more accurately predict behavior at not only the cosmic scale, but the subatomic scale as well. This is not debatable, and yet the most predominant metaphysical models of today are mechanistic, and in turn deterministic, despite the fact that we know beyond a shadow of a doubt that there are very profound and significant limitations to this worldview.

So with all this advancement in Science in the last few centuries, and all the technological advancements that it has supported, where we essentially find ourselves is with two extraordinary powerful, and yet fundamentally incompatible, mathematical and theoretical models of how the “physical world” behaves. This rift in a nutshell stems from the notion that reality itself, as defined by some sort of measurable phenomena, in the quantum realm is determined not only by the act of measurement itself, but that this outcome, again as defined by some sort of value or property related to the phenomena being measured (spin for example) is not even deterministic in the classic (Newtonian) sense, but follows a probability distribution that is predictable only over the course of many measurements or experiments – this is Quantum Theory in a nutshell, which of course flies in the face of Classical Mechanics, i.e. Newtonian Mechanics..

Furthermore, to make matters worse, we also find that at the cosmic scale, notions such as space and time can only be construed, or properly understood, as “relative” values, values which depend upon the position of the observer, and the relative speed of said observer – Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity which predict the equivalence of mass and energy as well as the constant, fixed value of the speed of light. In General Relativity, these fundamental relative postulates regarding space and time are even further abstracted to incorporate gravity, which according to the theory is not a force necessarily, but instead effectively bends spacetime from which can be derived the (relative) position, mass and speed – the three measurement pillars at the cosmic scale – of an object.

Modern Science, as it stands today in fact, has yielded great developments and progress in our understanding of the physical world no doubt, standing at the very foundation of “modern progress”, and yet the theoretical constructs on top of which it is constructed (Quantum Mechanics and Classical Mechanics) are not only not fully deterministic in the Classical sense, but are also fundamentally incompatible with each other – philosophically and mathematically. And then we have the problem at the other end of the spectrum, at the cosmic scale, our ideas of space and time as discrete, measurable constructs has to be abandoned, or at best relaxed, in order for the underlying models to be complete and accurate. And at the other end of the spectrum in the sub-atomic realm, at the very core of “physical reality” you might say, objects (corpuscles) appear to be connected, correlated, in a way that is fundamentally non-Classical – analogous in many respects, oddly, to Eastern philosophical principles of underlying consciousness.

The standard position of course is that, at least from a Scientific perspective, is that our current models are better, more advanced, richer, and more verifiable than the philosophical (and theological) tenets of antiquity. And yet ancient man, at least as we have come to understand them as advanced societies emerge and a concerted effort was made to understand the nature of the world (philosophia), held beliefs that at their core reflected a deep understanding of the interconnectedness of all things, and that there existed an all-pervading consciousness of sorts from which the universe itself emanated, and that the distinction between inanimate and inanimate “things” stemmed from the existence of the Soul. And all this without anyone having to build massive particle accelerators in the depths of the earth to prove that it was so.

But yet even after all this advancement of Science, we are still left with some of the basic and fundamental questions that mankind has been asking ever since they could ask really. Philosophical questions regarding the essential nature of experience – or using Plato and Aristotle’s terminology, being – itself. Thus far, we have looked at a few attempts to answer such questions – e.g. the Metaphysics of Quality offered by Pirsig or the notion of the implicate order as put forth by Bohm. And with these conceptual frameworks we at least have coherent and intellectual sound metaphysical systems which do not abandon Science necessarily but incorporate and absorb it in a sense, and yet at the same time posit the existence of higher orders, or dimensions, of reality which can (and here we rest on Eastern philosophical tenets) be experienced, what we refer to as supraconsciousness, an idea that not only is expressed by Eastern philosophy but also rests at the very heart of what we have called mysticism, or the mystical arts. In this sense supraconsciousness is a state of being, a reflection of a higher order dimension of reality, which (intellectually and metaphysically at least) can co-exist somewhat peacefully with the predominant Western worldview which holds physical reality to be the highest order metaphysical principle, i.e. what we have called objective realism and causal determinism herein.

From this vantage point, from this extended or expanded metaphysics, the direct experience of supraconsciousness, as it manifests in the penultimate experience of the mystic, the end of the mystical arts as it were, represents a higher order reality, not one that is more true necessarily than the lower forms or paradigms, but one that is nonetheless higher from an intellectual, and really metaphysical perspective – in the Platonic idealist sense at least. In this sense we can look at these systems of metaphysics as (potential) ontological frameworks as well. In these ontological frameworks, frameworks that again do not reject Science but subsume it, the direct experience of the very ground of existence is not only possible but in some sense is an ontological first principle of sorts from which all other, lower order forms of being emanate, or originate, from– both intellectually and experientially, i.e. psychologically in a sense, as well. In this state of being, again our supraconsciousness, the perceiver communes with (i.e. yoga in the most literal sense meaning “union”) the source of all things – all subjects, all objects and even the experience of perceiving itself. This reality sits beyond the distinctions of subject and object, beyond the notion of perception as a separate and discrete act in the time and space continuum, and as such must be ontologically more significant than, a higher order intellectual framework than, subject-object metaphysics which sits at the very heart of Science and which requires division and separation as presumptive necessities.

An important point to be made here, at least for logical consistency sake and to counter the arguments of the so-called “orthodox” religious views which tout the sole divine authority of their respective Scripture, is that if you believe in the possibility of revelation itself, a notion which at least to some degree orthodox religious belief systems attest to given that there is an implicit revelatory aspect of the Scripture itself from which the authority of said Scripture is derived from, then one must acknowledge the possibility that direct perception of the divine by a human form is possible. In other words, there is an implicit mystical aspect to orthodox religions, in particular the Abrahamic religions, which all espouse the notion of divinely inspired Scripture, a feature that is most pronounced in Islam actually, somewhat ironic given the rigidity that Islam is known for, in particular in its fundamentalist interpretations

This dismissal of the reality of the mystical states, states which, at least from an Eastern theo-philosophical perspective, are effectively the birthright of all mankind and that which ultimately distinguish us as human, is pervasive not only in the Scientific community, but also in the orthodox religious community as well. While this dismissal is convenient from an intellectual as well as socio-political perspective, granting knowledge of reality to only those that are anointed or properly educated, their respective metaphysical frameworks simply do not account for the full complement of human experience, either as we as individuals have experienced it – through the experiences of dream and waking states, as well as higher order states of experience which all of us have had to at least some extent (even though we may not have identified them as such) – or how sages and mystics throughout the millennia of the history of civilized man, as it has been recorded in the scriptures across the world from virtually all religious doctrines, have described it over and over again.

These states of consciousness, i.e. our supraconsciousness, this higher order of reality that modern Science has such a difficult time explaining in really any capacity at all, can of course be found in virtually all of the Eastern theo-philosophical traditions, most notably in the Indian theo-philosophical tradition of course, but also can be found alluded to even in the Western theo-philosophical traditions as well – e.g. Plato as well as some of the Pre-Socratics, etc., from which the notion of wisdom, i.e. sophia, is associated with to at least some degree. While of course the existence or prevalence of these alternative intellectual and metaphysical paradigms do not by any stretch of the imagination make them true, and in fact the pure Scientist would argue that modern conceptions of reality are more true because they are in fact more “Scientific” (circular reasoning but still) and because they are more modern, nonetheless the prevalence of these alternative worldviews, along with the state of Science in regards to its seemingly inherent limitations with respect to being able to describe reality in a single, holistic model, not to mention its inability to explain or model the notion of consciousness itself, would certainly if nothing else leave open the possibility that some of these alternative worldviews should be (re) considered and that perhaps they may shed light, illuminate as it were, the nature of reality in a way that Science fundamentally cannot.

In searching for an intellectual paradigm that fully explains and incorporates all aspects of reality across the entire spectrum of experience (from the pure physical realm as explained by Science, to the psychological or mystical as explained by Psychology, Cognitive Science and Eastern philosophy, incorporating the notion of supraconsciousness) we must first identify the metaphysical and intellectual entity or idea that ties all these realms of experience together. The answer, or at least the best answer, in the spirit of Descartes, is the Self, or that cognizing principle which sits at the heart of any and all forms of, subjective, experience. From this central metaphysical principle – one which manifests itself in scientific models as the “observer”, in psychological paradigms as the “conscious” self, in Eastern philosophical traditions as the “Self”, and theological circles as the Soul, or God – one at least is in a position to construct an intellectual model that spans the entire spectrum of experience, providing a comprehensive and cohesive description of reality in all its forms and variants.

It is from this vantage point for example that Pirsig arrives at his Metaphysics of Quality, a system of metaphysics that expands the field of knowledge from the confining subject-object metaphysics which underpins the worldview of the West (and in some respects defines it) to a more expansive model which is based upon the notion of Quality as a central, pre-cognitive and all-pervading principle. In this system not only is subjective experience assimilated and integrated into the very foundations of the metaphysical paradigm (as opposed to relegated to the periphery as is the case with Classical as well as Quantum Mechanics), but also mystical states are incorporated and allowed for as well (even if only alluded to tangentially in Pirsig’s work), being represented as direct communal experiences of Quality itself in its most pure and unadulterated form – in his model as reflected in the experience of inspiration from which the very heart of Science, i.e. scientific hypothesis themselves, originate from for example.

This bridging of the intellectual gap as it were, incorporating subjective experience into the metaphysical paradigm, is an important starting point, and is essentially what Bohm accomplishes in his framework which posits reality as a series of inter-related, and ultimately hierarchical, models of order, with the physical realm being just one of many and which there exist (at least) two distinctive models for – the Quantum and the Classical – which both emanate from, or are precluded by, a higher order model that he refers to as the implicate order which is governed by its own set of rules and principles.

What Pirsig’s Metaphysics of Quality fails to incorporate however, but what Bohm at least tries to integrate at some level (even though he, like any philosopher, is constrained by the tools which he must use to perform his trade), is that the very nature of experience itself, given that it is entirely subjective by definition, must take into account the role of the human mind in defining the boundaries of such experience. This role of mind, or the psychological notion of self or “I”, is effectively where the intellectual lines are drawn between the fields of Physics, Psychology and Philosophy – Physics being primarily focused on measurement and “observables”, Psychology being focused on health and well-being of the self rather than on ontological questions per se, and Philosophy, or metaphysics really in this context (at least in its most pure and unadulterated form) having the intellectual latitude to be able to focus purely on the abstract, operating in the realm of ideas directly in a very real sense (no pun intended).[1]

Bohm, and his colleague Basil Hiley, definitely make a valiant effort to try and bridge this seemingly impossible chasm, taking metaphysics to revolutionary places with their firm grasp of, and wholesale integration with, both Quantum Mechanics and Classical Mechanics, both the very height of the scientific domain as well as the very source its challenges with respect to ontology. Hiley, in describing the import and significance of Bohm’s metaphysics, argues that if reality is viewed in terms of process rather than a fixed, discrete “thing” or “object” (or set of “things” or “objects”), as it is so described with the notion of holomovement which underpins Bohm’s metaphysics, subsuming space and time as mental constructs that facilitate the (mathematical) description of physical reality and nothing more, than the two seemingly disparate intellectual domains of Physics and Psychology – the res extensa and res cogitans of Descartes respectively – can in fact be integrated into one holistic intellectual system which integrates both mind and matter:

Our proposal is that in the brain there is a manifest (or physical) side and a subtle (or mental) side acting at various levels. At each level, we can regard one side the manifest or material side, while the other is regarded as subtle or mental side. The material side involves electrochemical processes of various kinds, it involves neuron activity and so on. The mental side involves the subtle or virtual activities that can be actualized by active information mediating between the two side.

These sides […] are two aspects of the same process. […] what is subtle at one level can become what is manifest at the next level and so on. In other words if we look at the mental side, this too can be divided into a relatively stable and manifest side and a yet more subtle side. Thus there is no real division between what is manifest and what is subtle and in consequence there is no real division between mind and matter. [2]

This description of reality, from a Physicist no less, not only represents an interpretation of Quantum Theory as it relates specifically to the concepts of implicate and explicate orders as described by Bohm, but also embeds within it the notion of active information which underpins Bohmian Mechanics and helps “explain” how it is that the fundamental constituents of nature, i.e. subatomic corpuscles, can be seen both as waves and as particles depending upon the perspective of the experiment, and in turn the perspective of the experimenter. By placing greater ontological significance and emphasis on the process of experience, i.e. the act of cognition (as does Pirsig to some extent with his Metaphysics of Quality, i.e. Dynamic Quality versus static Quality), a metaphysical paradigm where mind and matter can in fact be bridged can be established.

This fundamentally philosophical problem is the very one that is confronted by anyone who tries to interpret what Quantum Theory really means, map it at some level to physical reality, where the role of the observer, the role of mind, cannot be completely ignored when trying to determine how a final quantum state is perceived which must account for the setup and measurement apparatus itself. It’s this element of mind, the question of correlation between the relationship of the two individuals who set up the two sides of the EPR Paradox measurement apparatus, that in fact lays at the heart of the final loophole that cannot be theoretically discounted with Bell’s Theorem, namely in illustrating that the final state of correlation that is observed between two once integrated and seeming classically separated quantum systems cannot be explained by some predefined, predetermined and fundamentally pre-correlated mental state of each of the individuals who (presumably independently but that’s the relevant problem at hand) setup and perform the two different but related experiments which reveal the entangled state of the quantum systems, calling into question some of the basic underlying assumptions of Classical Mechanics.

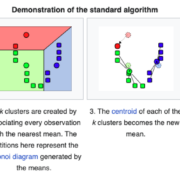

In an altogether different approach, interpretation as it were – of Quantum Mechanics at least – is the view posited by Hugh Everett, where an observable quantum state corresponds to what he refers to in typical physicist/mathematical jargon as the relative-state formulation of Quantum Mechanics which posits that a given quantum state exists out of the possibility of all potential observable states (or “realities”, which is a bit of a misnomer but is how his theory has come to be interpreted), all governed by what he refers to as his Universal Wave Function which describes the current and all future states of the entire universe.

In this case, Everett’s metatheory directly incorporates the role of the observer into his model, at least mathematically speaking, as a state machine which can perform some level of deductive reasoning and which has some level of access to prior states, i.e. memory. Again, the notion of the observer, the notion of mind in some aspect or another, is directly incorporated into this formulation of Quantum Mechanics, or Interpretation of Quantum Theory as the case may be, thereby circumventing not only the measurement problem, which plaques prevailing orthodox interpretations of Quantum Theory, but also rendering the need for wavefunction collapse obsolete and unnecessary. But while arguably Everett did not necessarily intend to wade into metaphysical waters necessarily, his interpretation of the underlying mathematics of Quantum Theory does in fact solve some very basic challenges of the theoretical model, while arguably raising some other ones (like for example the idea that multiple universes, or realties, may exist at any given time which gave rise, and credence to a large extent, to the “multi-verse” idea). The elegance of the relative-state formulation idea really, is that it allows for a fully coherent pseudo-ontological description of reality in a way, even if again it is not necessarily intended to do so.

Contrast this more purist, mathematical approach in interpreting Quantum Theory, one of if not the greatest breakthrough in the realm of Physics in the 20th century, with Bohm’s interpretation, what some refer to as Bohmian Mechanics. In Bohm’s view, the state of the system within which an observation is performed is said to be governed by a “conditional” wavefunction, a wavefunction that is in some sense a subset of the more holistic wavefunction which includes the behavior not only of the system that is being measured or observed, but also the apparatus and act of measurement itself, i.e. the observer (be they mechanical or mental/personal). This is how Bohmian Mechanics sidesteps the measurement problem, it incorporates the act of measurement into phenomena governed by the same Schrödinger wave equation, except one that is a “superset” in some sense of the conditional wavefunction which only defines the behavior of that which is being observed, independent of the mechanism of observation itself.

This idea of the conditional wavefunction, combined with the hidden variables which are the actual initial positions and momentums of the particles in the initial quantum state which in turn determine the final form of the wavefunction after the experiment is performed, is conceptually how wavefunction collapse is accounted for in Bohmian Mechanics. Whether or not the conditional wavefunction as Bohm (and Hiley) describe it exists as an actual measurable and definable phenomenon, or whether it simply exists as a theoretical construct that must exist in order for Bohmian Mechanics to be fully coherent and consistent, is almost besides the matter. By incorporating the role of mind, i.e. the observer, as well as the act of perception itself, back into the conversation about what is actually going on when a quantum observation is made, Bohmian Mechanics in fact (by design) forces us to consider that the act of perception itself as a first order principle that we should be looking at, from a metaphysical perspective at least, not the specific explicit order which may or may not be applicable to a given domain of experience.

Quantum Theory as interpreted, or explained, in Bohmian Mechanics is theoretically, and mathematically, sound and there is no need (conceptually at least) for any artificially induced wavefunction collapse, thereby providing at least the beginnings of a coherent system of metaphysics, an ontological foundation even, by which Quantum Theory may be understood. In addition to Bohmian Mechanics then, what Bohm effectively does by introducing the notion of hierarchical orders of reality – declaring the existence of an implicate order which holds ontological significance over the various explicate orders which reflect (various aspects of) the physical domain – is venture into the domain of ontology quite directly, provide an explicit (intellectual) bridge between two seemingly contradictory theoretical models of reality, systems of metaphysics, articulating a reasonable and viable explanation of reality itself, albeit from a mechanical perspective, as to how they both (Classical Mechanics and Quantum Mechanics) can be empirically true and valid while at the same time contradicting each other in basic tenets and assumptions (like locality for example), and at the same time reflect a higher order notion of reality which is fully coherent and consistent, albeit abiding by a completely different set of “laws” so to speak than the “lower” order forms.

In this way, and in fairly courageous fashion one might add, Bohm refuses to yield to the standard Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Theory which simply posits that the math underlying Quantum Mechanics is simply a model for solving equations and nothing more and should not be looked upon as having any sort of ontological relevance at all, while at the same time not necessarily venturing into pure idealistic philosophy necessarily, but first metaphysics and then ontology, all the while staying true to the rational, mechanical and ultimately mathematical models that underpin Classical and Quantum Mechanics, the two grand pillars of modern Physics. He accomplishes this by emphasizing the importance of metaphysics in and of itself, in very much the same vein as Aristotle some 2500 years ago (i.e. first philosophy), emphasizing not the physical realms themselves which are described by, modeled by Classical and Quantum Mechanics, but – from a higher order perspective – the grounding of existence being a continuous process of unfoldment of higher order realities into lower, physically manifest, forms of reality governed by distinct and (potentially) separate laws or order, thereby establishing a coherent and logically consistent ontological system which incorporates the prevailing mechanistic models of 20th century Physics.

In Bohm’s ontological framework, it is this concept of active information, his notion of quantum potential, which represents this non-local force in the quantum realm which underpins the reality of the subatomic world, and by extension all of physical reality. And from his perspective, reality at all levels of order or manifestation are more accurately described in terms of the constant process of unfolding and enfolding of explicate orders from and back into higher order realities, i.e. implicate order(s), an unending process which is perceived by us as various manifest physical realities in some way. This is Bohm’s undivided universe, which is best described as a process of constant unfolding, what he termed holomovement, which incorporates mind, which is required for any act of perception to take place, directly (back) into the model as it were, effectively pointing to an all-pervading consciousness which underlies the universe, within which mind is but one (subtler) aspect. In way, at least from an ontological perspective, Bohm ends up in a very similar place as Everett, albeit their approaches – metaphysically at least – are quite different.

Contrasting Bohm’s metaphysics with Pirsig’s Metaphysics of Quality which divides the intellectual landscape into two main driving forces, each of which is (at least tangentially) related to the very basic cornerstone notion of Quality – the Dynamic and the Static, the former reflecting the more “Eastern” conception of reality, the direct intuitive perception of “truth” or “knowledge”, whereas the latter form of Quality is, well static, in the sense that it reflects the more foundational intellectual forms of mankind which are more resistant to change and which provide the basis for a well-functioning (global) society, Neither Bohm’s ontology, nor Pirsig’s metaphysics (and the two intellectual models no doubt differ in this very fundamental way in terms of scope and intent, one with a focus more on ontology – Bohm – and another on metaphysics – Pirsig) addresses directly the nature of the very foundation of their respective intellectual models, no doubt preferring to leave that question up to the theologians which is probably the proper domain for such questions. Pirsig claims (rightfully so) that Quality itself in its most pure, unadulterated form (Dynamic Quality) rests beyond any intellectual grasp, betrays any form of definition (much like the Dao or Brahman in the Eastern philosophical traditions), and Bohm’s work focuses more on the underlying descriptive order, or workings, of reality as a continual process of change, unfolding and enfolding between different dimensions so to speak (which also betrays characteristically “Eastern” attributes with respect to the notion of change and process being the most ontologically significant aspect of reality), rather than attempting to describe the nature of that which sits behind the process itself, the man behind the machine so to speak.

What we are left with effectively, in the search for an ontological paradigm in the Western intellectual landscape which accounts for the entire spectrum of human experience, across the physical and psychological domains, is a chasm of sorts that relegates questions of the very ground of experience itself, the notion of supraconsciousness which rests at the very heart of Eastern philosophy, to theology, or at best to philosophy. And perhaps rightfully so, as these intellectual systems of the West, even the most abstract and comprehensive of them, are essentially systems of metaphysics more so than ontological frameworks necessarily, and most certainly not theological systems or “spiritual frameworks” per se. They are all products of Enlightenment Era philosophy, and even more so the revolutionary advancements of Science in the 20th century that have given us Relativity and Quantum Theory.

To a certain extent, this gives these systems strength as they are built on these modern Scientific developments. But from another perspective, from the perspective of say an ancient philosopher, these systems – given the context within which they emerged – are quite limited in the domain within which they are applicable. Very strong with respect to explaining physical systems and modern intellectual paradigms that are grounded therein, and quite weak really as we have seen with respect to explaining really anything that does not belong to Science proper. For example, the systems we have looked at throughout this work, and specifically in this Chapter, do not explicitly account for the qualities, or nature, of Mind in the true Eastern philosophical sense of the term. Nor, again given that they are systems of metaphysics and are natural extensions “mechanical” theories, do they or can they be used to account for, from a “spiritual” perspective, the potential reality of what we have come to refer to in the West as pertaining to, or of the, “Soul” – the Soul as a cognitive and experiential “being” through which not only is the physical realm manifest and experienced, but also through which the mystical realm is experienced as well.

This notion of the Soul in the West equates at a very basic level with the notion of Mind from a Buddhist perspective, the Intellect from a Neo-Platonist perspective and the Ātman of the Indian theo-philosophical tradition, all of which represent – in their own respective theo-philosophical systems – the individual reflection of the cosmic. Man made in the image of God, one of the very basic tenets and fundamental assumptions really, of all of the Abrahamic traditions. In turn, this notion of the Soul becomes, from a metaphysical perspective, the specific corollary to very fundamental and primordial ordering principle of the Universe, which we find in every cosmogonic and metaphysical conception of the reality in all of the ancient mythological creation narratives of all Eurasian peoples and civilizations in antiquity that we cover in this work in fact. All peoples and civilizations in antiquity it would appear, presume that the Universe is an ordered place and that the greatest power in the Universe, the greatest and the most prolific, is that which provides order to chaos. This is why Zeus is so revered in fact, and all the great gods in antiquity, Yahweh being no exception, played the same very critical role.

And man being in the image of the divine, the ordering principle of man – the Soul – is the analog to the divine in our realm, the realm of Earth and Man. In virtually all of the ancient theo-philosophical systems, the ones in Eurasia that we explore in this work, the Soul plays a fundamental role in the “ordering”, “comprehending” and “realizing” aspect of existence as seen from an individual perspective. And this Soul again has a direct cosmic counterpart, or analog – what penultimately in the West came to be known as Logos which more or less becomes equated with God in the Trinity, arguably the very pinnacle of metaphysical and ontological conceptions in the Western theo-philosophical tradition.

From this vantage point at least, the systems of metaphysics that we explore in this work, the ones grounded in 20th century Physics, do not cover or deal with this very fundamental and basic metaphysical (and ontological) construct that permeated not just theo-philosophical thought in antiquity, but really all thought in antiquity. In the ancient theo-philosophical traditions, particularly those of Indo-European heritage (the ancient Greeks and Indians basically), the Soul was arguably the defining metaphysical entity or principle upon which the theo-philosophical tradition hung together – the hub upon which all of the various branches of the respective theo-philosophical system sat upon you could say. It was the Soul in the end that defined what it was to exist, what it was to be, and in turn was the filter through which “being” itself was experienced and in turn provided for the fundamental connection to the all-pervading substratum of existence itself.

So in this sense, despite the power and specificity of the systems of metaphysics of Bohm, and Everett, and perhaps to a lesser degree Pirsig, they nonetheless lack this cornerstone metaphysical principle upon which any truly comprehensive, complete really, notion of reality must rest. To Aristotle and Plato no doubt, the Soul was everything really, the vessel within which all life was to be perceived and/or conceived. To both Plato and Aristotle, despite their differences, the Soul nonetheless provided the very foundation upon which their respective theo-philosophical system was constructed. It was that that which gives us life, that which animates us (animus, i.e. Soul), thereby representing the primary intellectual vehicle, metaphysical principle really, through which experience in all its forms must be viewed or conceived of.

To the ancient philosopher then, this conception of a person, or individual, in any grand philosophical system, being represented by simply some entity or thing that is simply “observing” and taking measurements, would no doubt seem ridiculous. And yet this is the unintended consequence of our progress in the West with Science, that any notion or idea, any principle, that smacks of theology, anything that cannot be empirically proven to exist in fact, must thereby fall outside of the domain of Science and as such isn’t’ included in even the broadening of the intellectual frameworks, the systems of metaphysics, that we have looked upon that have been established in the last few decades to address these basic ontological shortcomings of Science.

But without the notion of the Soul there is only so far these systems can go, like circling around the problem but never really getting to the heart of it. Because there is no defining principle, no metaphysical or ontological entity or construct, upon which to rest the very pinnacle of experiential reality (what we call supraconsciousness) from and out of which – at least according to the Eastern philosophical traditions – all forms of reality and existence emanate and originate from.

[1] Such distinctions and varying expertise in these fields of study in fact, all of which are arguably required to be drawn upon to come up with a truly cohesive and comprehensive ontological system, is in fact one of the very reasons why we find most modern conceptions of reality – as defined within each one of these domains – to be lacking. Drawing from all of them, while still staying true to each of them, is a difficult task intellectually to say the least, and one which very few, if any, modern scholars are actively working on.

[2] Basil Hiley: “Quantum mechanics and the relationship between mind and matter”, in: P. Pylkkanen, P. Pylkko und Antti Hautamaki (eds.): Brain, Mind and Physics (Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications), IOS Press, 1995, ISBN 978-90-5199-254-0, pp. 37–54, see pp. 51,52. Sourced from Wikipedia contributors, ‘Basil Hiley’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 14 November 2016, 09:06 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Basil_Hiley&oldid=749435694> [accessed 14 November 2016]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!