Overarching Themes: The Laurasian Hypothesis and a New Metaphysics

While we have attempted to describe the nature of the work, and its underlying “purpose”, in Aristotelian terms[1], whenever the author stops to think about it, or whenever he is asked “why” he’s doing it, there never appears to be a clear and concise answer to the question, and least not to the author even though a logical and rational response can be given. In fact, it is arguably a reflection of such a basic materialistic and self-obsessed capitalistic society that we live in (that the author lives in at least that is the very source of a) the question itself, no one would consider creating art for art’s sake, and b) a reflection of this basic philosophical quandary that the author is attempting to uncover and potentially solve that the answer that he provides is never really satisfactory to anyone who asks.

In brief then, it’s never really not quite clear to the author why we should complete such an extensive and broad reaching work such as this. The author certainly never set out to do such a thing at the start, and arguably had he known how significant an effort it was we never would have embarked on it to begin with (but the same could probably be said for many works of creation so in that sense this is no different). Nonetheless, here we are. So “go figure” is perhaps as good an explanation as any that can be found to explain the “situation”, if we may call it that. But the how we got here is a point worth noting as well. The means of production as it were, especially given that the author did not embark on a this extensive a work to begin with. In fact, quite the contrary, after Snow Cone Diaries we thought we were “finished”. But what we found was that once we started writing and producing material on a broad range of topics, mostly regarding theo-philosophical development in antiquity, each topic led to another related one, which in turn led to another, and another and so on and so on until a very broad and far reaching chain was developed and certain patterns emerged that the author could not find in any of the existing literature.

And so it was simply by the constant authoring and writing (and publishing draft material periodically on the web)[2] of small chunks of thought as it were, essays really, that after a long period of time of relatively consistent effort on topics that were all of interest, and all connected in one way or another, and all authored from a perspective that the author thought was unique, it became clear not only that such a work was possible, but almost that it was essential and that “it had to be done”. It’s hard to explain really, but perhaps it is not much of a stretch to imagine that many authors have similar experiences with their creative process, and indeed such was the reliance and import of the Muses of ancient Greece who were believed to inspire the mythic poets of old in fact.[3] From a pure academic perspective, which is shorthand for Western intellectual and Scientific perspective, there are at least two prevailing sentiments or theories that are put forth in Parts I and II of this work that the author believes should force us to recast or reformulate modern views and perceptions, our fundamental understanding of really, the relationship between and among the prevailing mythos (primarily cosmogonic, i.e. creation narratives and mythologies) and philosophical traditions of the respective civilizations that are covered in this work – namely the civilizations of the “West” as exemplified by the ancient Sumer-Babylonian, Egyptian, Persian and Greco-Roman cultural traditions, and the civilizations of the “East” as exemplified by the Indo-Aryans – as reflected specifically in the literature attributed to this ancient people namely the Vedas and the Upanishads, and the philosophy put forth by Buddha – and the philosophy of the ancient Chinese peoples as reflected in the Yijing, the Dao De Jing and the other ancient Chinese “Classics”.

First, as we scale our view out from a regional and historical perspective, looking at the overall development of human intellectual developments from a more global, or perhaps more specifically a more integrated “Eastern” and “Western” view, we find and explore the meaning and definition of what we term “Indo-European philosophy”, a term we define as the set of beliefs, the underlying theological and philosophical views, which underpin not only the Hellenic philosophical tradition which basic provides the foundations of the Western intellect (which we know borrowed at ;east to some extent from its “direct” neighbors to the East, i.e. the so-called “Near Eastern” traditions which much of the academic material refers to as “Oriental” but really consist of the Sumer-Babylonians and Persians/Iranians mostly), but also the philosophy of the Indo-Aryans as well, which is reflected most directly in the Upanishads but which also forms the basis of Buddhist philosophy as well. All of these theo-philosophical traditions emerge in the historical record throughout Eurasia, from the Mediterranean to the Indian subcontinent to the Far East, in the middle of the first millennium BCE or so, give or take a century or two, therefore representing the age of man that we refer to as the “Axial Age”.[4]

Second, as we analyze and study the various theo-philosophical traditions that emerge across Eurasia and the Mediterranean in the first millennium BCE, the author concludes that the similarities and common threads of thought that we find in these various theo-philosophical traditions represent not the specific borrowing and exchange of ideas, but the remnants of ancient belief systems that that reach much further back in antiquity than considered by most scholars and academics of ancient history.[5] One thread of commonality already mentioned is traced back to a distinctly Indo-European theo-philosophical system that runs parallel (backward in time) to the spread of Indo-European languages, a subject of theoretical philological (study of languages) inquiry in the last century or so which provides the basis for the term “Indo-European”, a language family which is known to include Sanskrit, Greek and Latin among other languages that were prevalent in the Mediterranean and Near East in the 4th, 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE.

We extend this philological theoretical construct, i.e. “Indo-European”, to the domain of “theo-philosophy”, arguing that the commonalities that we find throughout the Indo-European landscape from a theological and philosophical perspective are the result of the shared theo-philosophical ancestry of these peoples that populated this region in antiquity rather than the result of cultural borrowing and/or some type of collective unconscious (in the Jungian sense), positing the existence of parent theo-philosophical belief system of sorts that runs parallel with Proto-Indo-European language that was inherited, or at the very least strongly influenced, the (spoken) languages of the Greeks, the Indo-Aryans (Sanskrit speaking), the Sumer-Babylonians and the Persians (the Indo-Iranian family of languages). We extend this theory to include not only these people that shared linguistic characteristics with each other, but also to include the (ancient) Egyptians as well, an ancient civilization that although clearly has a different history and origin that the ancient Hellenic people, i.e. the ancient Greeks, it nonetheless evolves from a cultural and theo-philosophical standpoint very much aligned with the ancient Greeks after the 2nd millennium BCE or so when the two cultures begin to have very constant and persistent contact with each other.

The thesis is that this Proto-Indo-European theo-philosophy provides the basic theological and mythological structure, and the underlying and associative meanings which then morph into philosophy proper as writing becomes more prevalent in the first millennium BCE, providing the foundations from a theo-philosophical perspective for the majority of Eurasia in antiquity – outside of the Far East/China basically which in the author’s view reflects an even older theo-philosophical tradition, older than Proto-Indo-European that is. Along with this Proto-Indo-European theo-philosophical belief system, we propose an even deeper lineage across all of Eurasia that naturally presents itself as one looks across these classically “Eastern” and “Western” divides and invariably finds many common intellectual threads and similarities between the different metaphysical and philosophical systems. This theory effectively follows the lines of the Laurasian mythos hypothesis of Harvard Sanskrit scholar and professor Michael Witzel that he outlines in his seminal work, Origin of the World’s Mythologies, but we extend the hypothesis from a simple shared narrative as it were that explains the shared cosmologies of these ancient peoples throughout Eurasia, to a shared intellectual worldview of sorts, one which provides the foundations for theo-philosophical systems that emerge in the first millennium BCE that we find reflected in the earliest works of these respective “Eastern” and “Western” early civilizations when writing first develops and these belief systems are first codified and philosophy in antiquity starts to take shape across Eurasia.

These developments establish what we have to come to refer to throughout this work as “Eurasian philosophy”, an altogether unique perspective on philosophy in antiquity that brings together both Western philosophy and Eastern philosophy (in antiquity) under a single umbrella so as to emphasize the fundamental relationship of these seemingly disparate and distinctive worldviews, worldviews that nonetheless share many common motifs and themes which point to common (intellectual) lineage from the Neolithic Era which our modern understanding of genetics and human migration sheds significant light on. From this more broad and deeper perspective surrounding these ancient bodies of knowledge that we find in the first extant set of literature that appears in Eurasia in antiquity, we can recognize Western and Eastern philosophy as representing two different streams of thought yes, but also at the same time as individual manifestations and interpretations of a single, shared, base of wisdom that reaches deep into antiquity. It then shows up in this so-called “Axial Age” throughout Eurasia in various forms that are socio-politically, linguistically and geographically distinct, but nonetheless representative of a body of knowledge that comes at least to some degree from a shared heritage, providing insights into the mind of pre-historical man that have never really been explored before, allowing for (calling for really) a new approach and framework for understanding ancient philosophy from which our modern designation of “Eastern” and “Western” comes from.

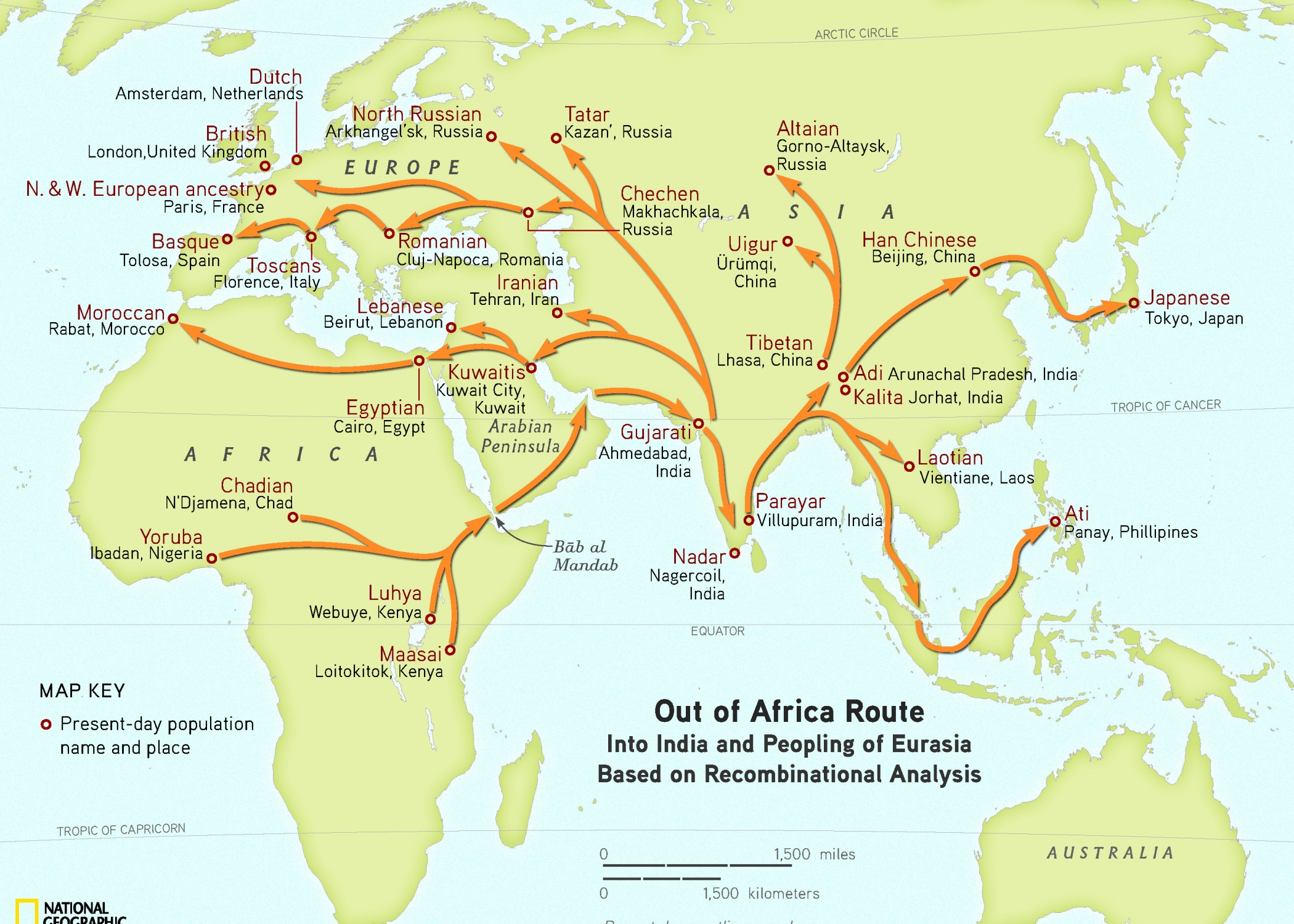

This Laurasian hypothesis, which is in effect a deep, pre-historical shared ancestry hypothesis for the ancient peoples of Eurasia, not only aligns quite well with the archeological record, as evidenced for example in the Cave art findings[6] as well as the Venus figurines motif[7] that we find spread across Eurasia in the of the Upper Paleolithic (circa 50,000 to 10,000 years ago), but also aligns with what we know is the common lineage from a genetic standpoint that all these ancient peoples share, having discovered in the last decade or so that all European as well as Asian peoples (and Americans as well) all stem from a relatively small population of homo sapiens that migrated out of Africa roughly around 100,000 years ago and which in turn gave rise to an Eastern expansion some 60,000 to 70,000 years ago give or take.[8]

While this reaches very far back into ancient history, much further back than we have a record of from an historical perspective of course, and into a time period of history where even the archeological record is quite sparse, from the author’s perspective these common theo-philosophical threads that we find across Eurasia as exemplified in the very similar systems of metaphysics and theology, and underlying themes of numerology, skepticism and idealism that we find predominant in both the Yijing and the Dao De Jing from the Far East as well as in the theo-philosophy of both the Pre-Socratics (e.g. Heraclitus, Parmenides which then dovetail and influence the theo-philosophy of Plato) as well as the Indo-Aryans and the Indo-Iranians is best explained by a shared common ancestral hypothesis, i.e. the Laurasian hypothesis, coinciding of course with a much more lasting and persistent theo-philosophical system which is typically attributed to these “pre-historic” peoples, rather than any of the alternative theoretical hypotheses that have currently been proposed, with perhaps the “cultural borrowing” and “cross pollination” hypotheses being the most widespread despite the lack of evidence surrounding it.

We see traces and threads of this shared common ancestral theo-philosophical belief system from the late Upper Paleolithic throughout Eurasian antiquity as reflected in the underlying worship of the great god of the heavens as the greatest of all deities and presider over the natural world, the emergence of the “ordered” cosmos from a “watery, dark abyss”, the myth of the primordial “cosmic egg” from which the earth and heavens are born, sacrificial worship in general to anthropomorphic deities that are representative of various aspects of nature, the worship and veneration of ancestors, i.e. hero worship, etc. We find more or less most of these theo-philosophical features persistent throughout virtually all of these Eurasian cultures in the first millennium BCE as these distinctive civilizations begin to emerge and flourish, as respective areas of imperial influence start to spread and expand and spheres of socio-political influence along with it, and in turn as the respective theo-philosophical belief systems become codified and systematized as writing is invented in order to support these vast empires with a more cohesive and synthesized “culture” to a large extent.

While forms of worship and the perspective on the “divine” are very different in ancient China than in the area of Indo-European influence no doubt, the systems of metaphysics and the core flavor as it were of the underlying theo-philosophical systems that emerge in these geographically distinct regions for which we have no evidence of cultural contact points to either a) some sort of shared common theo-philosophical source from which these belief systems stemmed from that aligns with human migration patterns and settlement (Witzel’s Laurasian hypothesis mapped to philosophy rather than mythology), or b) the existence of an eternal and ever present theo-philosophy of sorts which aligns with Jungian collective unconscious, or c) some combination of the two. These facts, these similarities and common ground from a theo-philosophical perspective across such a wide expanse of geography in regions that we do not have any evidence for direct cultural or economic contact at the very least forces us to consider whether or not the similarities and commonalities are shared precisely because they all stem from a common source or origin which reaches much further back into antiquity than is previously thought and again reflects a theo-philosophical tradition, and a corresponding intellectual capability and transmission mechanism, of ancient man that reaches much further back into pre-history than is commonly held in academic and ancient historical circles today.

While the Laurasian hypothesis then might seem perhaps somewhat far-fetched upon first glance, upon deeper reflection and analysis, at least from the author’s perspective having studied such topics over a long period of time, the hypothesis starts to look a lot more possible, and in fact perhaps even probable, once the ancient theo-philosophical systems are looked at through a broader and more expansive lens and when the context of human migration patterns, and the overlapping archeological evidence as thin as it is, is all taken together as a whole.

Another one of the fundamental topics and themes underlying this work, in particular covered in Part IV of this work, material devoted to ontological considerations[9], is that how we define reality, what we consider the basis and boundaries of knowledge itself, must encompass psychological and perceptive “conceptions” in order to be considered “complete”. This is, from the author’s perspective, not only an absolute requirement from a rational and logical perspective but also from a Scientific perspective as well as reflected in some of the implications of Quantum Theory, one of the most revolutionary Scientific “discoveries” of the modern era.

In this author’s view, this necessary epistemological expansion as it were, is based not only upon the state of Scientific knowledge in the 21st century as reflected in the current state of Physics as reflected by the prevailing truths of Classical Mechanics as well as Quantum Mechanics, but also based upon what we consider to be the basic, self-evident, truths surrounding the reality of states of consciousness that are evoked and produced by the art of meditation, what we refer to as the supraconsciousness throughout this work. We will show that these states of Being as it were, borrowing the terminology used by the earliest Hellenic philosophers such as Parmenides, Plato and Aristotle, represent the very source of Western philosophical and intellectual tradition itself and yet have been effectively lost from an epistemological perspective as the state of reason, and theology in general, have evolved over the last 2500 years.

These pure states of unadulterated consciousness, i.e. supraconsciousness, that are effectively experienced by advanced mystical practitioners, represent the very foundation of mysticism in all its forms and are in the author’s view indicative of a reality that exists beyond the realm of subjects and objects[10] and as such should, and must, be incorporated into any comprehensive and complete description of knowledge (i.e. epistemology) that is to serve mankind going forward such that our relationship not only to ourselves (viewed as “spiritual” entities rather than physical biochemical and neurological processes) is better understood and comprehended in order to support a more “fulfilling” and “nourishing” life experience, arguably the goal of each and every one of us, but also that our relationship to each other and the natural world, i.e. our “environment”, is better understood to effect a more harmonious and balanced existence for human society as a whole.

These states of Being, the so-called supraconsciousness, are looked at in detail not only within the context of the Indian philosophical tradition as a whole, but also within the context of the well documented and studied spiritual practices and experiences of the 19th century sage Ramakrishna[11], the teacher and spiritual inspiration for one of the most influential and prominent figures of the modern Yoga tradition in the West, i.e. Swami Vivekananda. The reality of the supraconscious is a constant theme throughout this work and is explored in detail in Part IV and V of this work and from the author’s perspective has significant implications on not just our definition of knowledge itself, but also on the place of theology, morality and ethics, as well as metaphysics (again what is referred to as first philosophy following the tradition of Aristotle) within the context of any inquiry and study of the nature of reality.

We argue that the initial conception of knowledge by the earliest Western philosophers, i.e. the Pre-Socratics, Plato and Aristotle specifically, incorporated (or at the very least did not altogether dismiss) the experiential reality that was reflected in these so-called “mystical” experiences, even if they did not explicitly discuss or analyze them directly. This is reflected for example in Plato’s conception of knowledge, i.e. his epistemology, as divided into the world of Being , which was eternal and changeless, and the world of Becoming which is characterized by constant change or movement – a metaphysical and theo-philosophical conception which in fact forms the basis of Aristotle’s epistemology, i.e. his notion of being qua being.[12]

We further argue that this notion of change as the basic underlying principle of the natural world is not only a characteristic of early Hellenic philosophy, but is also a prominent theo-philosophical construct of ancient Chinese philosophy, i.e. the philosophy of the Far East in antiquity, providing the basis as it were for the argument of a shared theo-philosophical heritage that reaches much further back in antiquity than is typically considered and which connects all of the ancient peoples throughout Eurasia to at least some degree. As such, one of the overarching themes of this work is that in looking at the roots of rational inquiry in the West, through the looking glass as it were, we not only find a much broader and comprehensive definition of knowledge and reality which from the author’s perspective is a more accurate and complete depiction of the full state of human experience as well as the natural world and surroundings which he finds himself in, but that it – as Quantum Theory forces us to do to a large extent – includes the exploration of the nature of the Soul and the full spectrum of cognitive experience, along with theological inquiry in general – all attributes that are completely absent from modern Science.

The author argues that this epistemological and metaphysical expansion or revision as it were, represents a requisite intellectual step that we must take as a species in order for us to progress and evolve in the 21st century and beyond in order to comprehend not just our fundamental interrelationship and interdependence upon each other for the achievement of individual, social and global harmony and order, but also a requisite step to truly comprehend and incorporate the fundamental interdependence and interrelationship we have with our natural environment and the planet as a whole, and in turn the universal cosmic order. For like it or not we have reached a point in our human history and evolution, and the state of the planet and the environment in fact, where our relationship to the environment is no longer just a philosophical or theoretical problem to be studied or debated, but that the dire state of the planet itself, our home upon which we (as well as all the species on the planet in fact) depend upon for survival, is a natural byproduct and outgrowth, a direct causally related phenomenon, of the very fundamental and basic misconceptions and misunderstanding of the nature of reality itself, the full exploration of which again is a core theme that underpins the bulk of this work.

As an illustration of the implications of such a reformulation of how we define reality and knowledge, rejecting what we call objective realism as inadequate and incomplete at best, let us look at how reality, and knowledge thereof, is conceived of by Aristotle, a discipline known in philosophical circles as epistemology and a constant theme throughout this work. While we cover Aristotle’s philosophy and metaphysics at length in specific chapters within this work, let’s summarize the principles here and in so doing look at how that compares to the objective realist, i.e. subject-object metaphysics conception of reality which provides the foundation of the Western intellectual and academic tradition, i.e. Science.[13] From a subject-object metaphysics perspective, a conceptual and metaphysical framework which rests upon the notions of causal determinism and objective realism, reality – and in turn (empirical) knowledge itself in fact – is fundamentally defined and characterized by various quantitative and qualitative measurement phenomena. Effectively if we cannot “measure” a thing, if its objective reality cannot be confirmed or verified, it doesn’t exist.[14] Science as it were sits at the very pillar of Western intellectual thought, with all other disciplines subservient to it, which is not quite the way the early Hellenic philosophers, our intellectual ancestors, conceived of the world to say the least.

From an objective realist point of view then, this work – this very Book which you hold in your hands right now and are reading (unless you are reading it electronically in which case we refer here to the tablet of device upon which you are electronically seeing these words and reading them upon) – is defined by various quantitative and qualitative measurements, each of which when combined together give us an empirically verifiable definition of what this work, this Book in its published form, actually “is”. What makes it “real”. How we describe it and upon which its reality in the physical world ultimately depends upon. In this sense we can say definitively, in a manner that is “verifiable by scientific methods of inquiry” that it consists of a certain number of words, a certain number of pages, a certain number of Chapters and Parts, that it was written by the author, that it was written using software called Microsoft Word, that it is written in the English language, that it was “published” in 2017, and even that it “references” and “quotes” various other texts in a variety of disciplines that were “published” by other authors at other dates and times in history.

In its final form, this work “exists” as a physical Book with a certain number of pages that is published by a certain publisher, that it weighs a certain number of pounds, that the pages are made up some form of paper that comes from some sort of tree perhaps, and that even a certain number of “copies” of the book are sold and delivered via various forms of mail and shipping centers. All of these are accurate “facts” and again, verifiable “truths” that describe this work and can help another person understand what it “is” from an objective realist perspective of course. However, it should be readily apparent to the reader that these facts, while true and descriptive at a very basic and “physical” level, leave out very significant “characteristics” of this work that make it unique and help us more fully understand, or comprehend, what this Book truly “is”. In more simple terms, it should be reality apparent that the aforementioned definition, while accurate and “descriptive”, is inadequate and lacking to a large extent.

As an alternative definition and description of this work, we look to Aristotle’s more broad conception of reality, how he defines the qualities of a “thing” which provide the basis for our understanding it as it were, a notion which is typically transliterated in modern philosophical circles as the somewhat misleading (and most certainly obtuse) expression being qua being.[15] To Aristotle, to understand the nature of a “thing”, the qualities which make it “real”, we must understand all of the ways, all of the “reasons”, which brought such a “thing” into existence. This is the topic that he covers in painstaking detail in his seminal work Metaphysics, or that which literally comes before Physics, as Aristotle initially conceived of the intellectual discipline, and what we refer to throughout this work, following modern Western philosophical parlance, as first philosophy.

From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy we find a good explanation of Aristotle’s epistemological framework, an intellectual framework which underpins his entire system of philosophy in fact – that knowledge of a thing, what Aristotle himself referred to in the Greek as epistêmê[16], must be underpinned by a complete and comprehensive causal based depiction of said object of understanding.

In Physics II 3 and Metaphysics V 2, Aristotle offers his general account of the four causes. This account is general in the sense that it applies to everything that requires an explanation, including artistic production and human action. Here Aristotle recognizes four types of things that can be given in answer to a why-question:

- The material cause: “that out of which”, e.g., the bronze of a statue.

- The formal cause: “the form”, “the account of what-it-is-to-be”, e.g., the shape of a statue.

- The efficient cause: “the primary source of the change or rest”, e.g., the artisan, the art of bronze-casting the statue, the man who gives advice, the father of the child.

- The final cause: “the end, that for the sake of which a thing is done”, e.g., health is the end of walking, losing weight, purging, drugs, and surgical tools.[17]

Knowledge then from Aristotle’s perspective, Aristotle’s epistemological framework as it were, as defined as the sum total of these four distinct types of causality, types which while are somewhat mutually exclusive are yet at the same time (from his perspective at least) exhaustive, not only consists of in the aggregate a much more broad conception of the notion of causality itself than we are used to in modern intellectual and academic circles in the West, but also allows for, and fundamentally supports, a much broader definition of reality itself as compared with the modern Western intellectual conception of reality which again is underpinned by the twin pillars of causal determinism and objective realism.

Aristotle’s conception of reality then, is based upon the very same notion of causality which underpins the prevailing intellectual paradigm of the West, i.e. the Western worldview, i.e. subject-object metaphysics, which as it turns out has significant ontological (i.e. the study of the nature of being or reality) implications – a subject which is covered at length in Part IV and Part V of this work. However, Aristotle’s notion of causality, the foundation of his epistemological framework, integrates the notion of form (in the Platonic sense), as well as purpose (teleology), into its very definition and therefore provides the basis for a much broader intellectual paradigm of understanding than what we are accustomed to in the West, one which comes closer (although not quite entirely) to the Eastern philosophical conception of reality in fact, one which includes the broader conception of what we have come to call consciousness itself.

Using Aristotle’s epistemological framework then, we can describe the material cause of this work, this Book, as the computer and software which was used to write the words and design the chapters and format the paragraphs, pages, footnotes, etc. The formal cause is the overall structure of the work, its intended form from an organizational perspective – the structure of the Parts and their respective Chapters – as well as the overall content of the work, i.e. its subject matter. The efficient cause is the author himself, the writer of the work, and the final cause, the purpose for which the work is completed, is for the advancement of human knowledge in general, not only as it relates to ancient history, but also as it relates to modern conceptions of reality of course.

Once we understand each of these causal aspects of how and why this work, this Book came into being as it were, what makes it real, each of them individually as well as all of them collectively together, we arrive at a proper and complete understanding of this work, i.e. everything there is to know about it. From the author’s perspective, this level of understanding gives the reader a much broader perspective, and in fact a much better and complete understanding of the work itself. While it includes the material aspects, it also includes the structural and formal aspects, as well as the teleological (the purpose) aspects of the work as well.

It is this last part, the purpose or meaning, that is actually almost entirely left out of any modern conception of reality in the West, conceptions that are grounded almost exclusively in the “physical” world and as such any sense of purpose is by definition excluded given that it has no empirical or objective value as such. While causal determinism and objective realism are very powerful guiding intellectual principles that have done a great service to humanity by furthering the development of Science as a discipline unto itself, our blind faith in Science has in fact left us with a somewhat unintended byproduct of a much narrower, and less holistic and less descriptive in fact, notion of reality itself. Hence the need for a revision of the underlying intellectual model as it were. Back to first philosophy in some sense.

As a further illustration of the effect of the broadening of this definition of knowledge we can look at Part IV specifically with respect to “interpreting” Ramakrishna using a fundamentally Western intellectual epistemological lens, one that although is broadened to include and recognize Psychology, as a theoretical framework for understanding the mind and its effect on behavior specifically (Freudian psychology specifically) nonetheless comes with boundaries and assumptions that altogether prevent us from fully appreciating, or even comprehending, Ramakrishna as an historical figure who has had such a profound effect on theology and spirituality across the globe since his death at the end of the 19th century – most of which is due to the teachings and organizations established by his most well-known disciple Swami Vivekananda.

The Soul to Aristotle is viewed through this epistemological lens of causality, this broad definition which although is not unscientific necessarily, it is one nonetheless which includes not just the formal aspects of change, i.e. the model as it were of that which is being shaped, but also of course the final cause as well which represents the underlying purpose or meaning behind anything that we are trying to fully understand, appreciate or in turn whose very existence can be understood. It is these last two aspects of causality that bring about the full meaning and appreciation of Paramhamsa Ramakrishna as a spiritual or religious figure, whose one true goal in life, the very reason or ultimate cause behind the sum total of his spiritual practices and his life in toto in fact, is the realization of God.

This assumption regarding the existence of God, and his (or her as the case may be) realization as it were, is not abandoned or ignored in this epistemological framework, but is (at least according to later theological interpretations of Aristotle’s metaphysics) integrated into the model as it were. This is the notion of the prime, or first, mover, which is equated with God, or Allāh, by the Muslim philosophical tradition for example. As such, understanding the driving force, the true meaning and significance of Ramakrishna’s spiritual practices using an Aristotelian epistemological lens, one can at least appreciate, and in turn interpret, his life and teachings within the context within which Ramakrishna himself lived as opposed to the somewhat contrived application of a Western intellectual materialistic and causally deterministic framework which invariably leads to confusion and/or total misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

In other words, while causal determinism and objective realism are extraordinarily valuable and powerful tools for understanding the physical world, it is nonetheless entirely inadequate as an intellectual framework for not just Quantum Mechanics, but also as an intellectual framework for understanding the full scope of human existence – an existence which must include some level an appreciation or acceptance of the wisdom of the East as it were. For it is from the wisdom of the East, of which traces can even be found in the ancient Western theo-philosophical tradition, that we find not just the fundamental belief in the existence of higher states of consciousness, i.e. supraconsciousness, but also the explicit belief that these states of consciousness can in fact be realized and that they in turn not only represent an aspect of reality, but also that they represent a higher order, or form, of reality itself – one which subsumes and transcends physical reality. This is not only the basis for all mystical practices and the experiences associated therewith which are the legacy the Eastern philosophical tradition, the Indian philosophical tradition in particular, but also represent the core underlying message of all the prophets of all the ages, Ramakrishna being no exception of course.

In brief, if the true nature of Being – an understanding of that which characterizes and underpins being in and of itself, what it means to be or exist – is what we are trying to understand, then causal determinism and objective realism are simply not adequate and a broader, and in fact a more ancient, ontological and epistemological system must be sought.[18]

[1] In Aristotle’s metaphysics, the notion of the purpose, or final end of a thing was a crucial element of his idea of knowledge itself, i.e. what has come to be known in philosophical circles as epistemology. The term in Greek is telos, a Greek word meaning “final end” or “purpose” which is one of the four pillars of Aristotle’s metaphysics which is based upon the notion of causality. Aristotle’s metaphysics is outlined in detail in Part III of this work in the section on Aristotle and substantial form.

[2] The blog along with many of the early drafts of chapters and content presented herein can be found at www.snowconenyc.com.

[3] Snow Cone Diaries was penned as “musings of Juan Valdez” as a veiled reference to such considerations.

[4] The term “Axial Age” which was coined by the famed German philosopher Karl Jaspers in the 19th century. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Axial Age’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 3 December 2016, 01:26 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Axial_Age&oldid=752746150> [accessed 3 December 2016].

[5] This theory of common origins sits in contrast to for example the ideas presented in the works by M. L. West in his book Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient published by Oxford University Press in 1971, arguably the most comprehensive work on the comparison of Greek and Indian philosophy ever produced authored by Thomas McEvilley entitled The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies published by Allworth Press 2002, as well as, albeit perhaps to a lesser degree, the ideas put forth by Walter Burkert in his article “Prehistory of Presocratic Philosophy in an Orientalizing Context” published in the Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy, Oxford University Press 2008.

[6] A more detailed look at Cave art findings can be found in the Chapter on the Pre-History of Man, in the Neolithic Era which is the last part of the Stone Age, can be ifound in the introductory section – Prologue – of this work.

[7]See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Venus figurines’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2 January 2017, 14:30 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Venus_figurines&oldid=757925423> [accessed 2 January 2017].

[8] See the National Geographic Genographic Project for details on the somewhat revolutionary discoveries related to the shared ancestry, and ultimate migration path, of ancient man at https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/human-journey/.

[9] Ontology is typically viewed from a modern western intellectual standpoint as the study of the nature of reality, or more precisely, being. The domain is related to, and most often considered a sub domain of, metaphysics – again from a modern, Western intellectual standpoint. While ontology is a relatively new word in the history of Western literature and philosophy, believed to have first been used in the early 17th century by the German philosopher Jacob Lorhard, it nonetheless has very deep origins and implications from a Greek linguistic and philosophical standpoint, the root of which stems from the present participle of the Greek verb “to be”, i.e. ὄντος, Romanized as óntōs. This term is explored in depth not only by Parmenides, but also by Plato with his notion of Being, and then in turn Aristotle with his notion of being qua being. The principle as a whole arguable forms the basic and underlying intellectual framework, and topic for debate and disagreement, of virtually all Hellenic philosophy. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Ontology’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 4 January 2017, 15:48 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ontology&oldid=758290928> [accessed 4 January 2017].

[10] This modern conception of reality as broken into subjects and objects is the outgrowth and culmination of some 2500 years of intellectual evolution in the West and is referred to throughout this work, following Robert Pirsig, as subject-object metaphysics.

[11] Ramakrishna (1836 – 1886) was born in West Bengal and is most referred to in this work using his full spiritual name which includes the epithet Paramhamsa, i.e. Paramhamsa Ramakrishna. A description of the meaning of the epithet Paramhamsa is given toward the end of Part IV of this work where various interpretations and/or explanations for Ramakrishna’s experiences are presented and analyzed in detail.

[12] Plato and Aristotle’s theo-philosophical systems are reviewed in detail in the relevant Chapters in Part II and III of this work, On Metaphysics and Theology respectively.

[13] This approach to using the content of the work itself in order to illustrate the import and meaning of the work is inspired by Carl Jung’s introduction to Wilhelm/Baynes classical translation of the I Ching (Yijing) where Jung actual “consults” the I Ching, i.e. uses it as a divination tool which is its primary purpose (the underlying philosophy and metaphysics was an implicit part of the work and not its primary purpose, being expounded upon only much later when the “Confucian” commentaries, i.e. the Ten Wings, which described the origins and various interpretations of the 64 hexagrams that constituted the core of the Yijing, was added to the text) in order to assuage some of his concerns that he harbored regarding writing the introduction itself given the nature of the text and given his background and profession as a “scientist”. In so doing, he described not only how to use the text, how it was traditionally used throughout the Chinese history, but also in many respects the underlying metaphysical, and psychological, interpretative value of the text itself, these qualities arguably being representative of the source of his deep and lasting interest in the text.

[14] Or even if its existence is not completely denied, it nonetheless lays outside of the intellectual framework of Science which again is based upon empirical and verifiable data and information only. In the intellectual disciplines where non-measurable and/or non-objective phenomena, like mystical experiences for example, are not altogether discounted, like Psychology for example, they are nonetheless not regarded as real per se, certainly not in the classic scientific conception of reality given that their existence cannot be empirically verified. instead these types of non-objective phenomena in these disciplines are for the most part regarded as theoretically and intellectual conceived notions or concepts that while may have utilitarian purposes in their respective and specific domains of study, cannot however be said to be a part of Science proper. While Psychology as a discipline is considered to be “scientific” by some (certainly by Psychologists for example), it most certainly lays well outside of the domain of Physics necessarily, the domain to which our modern notion of reality is ultimately tied to and rests squarely upon in fact. [The Psychological theories of Freud and Jung, each of which represent two ends of the Psychological theoretical spectrum in the modern era as it were, are covered in detail in Part IV of this work.]

[15] From the Greek to ti ên einai, or “the what it was to be”, a concept which underpins virtually all of Aristotle’s philosophy and represents the cornerstone of his epistemological framework, underpinning his rational approaches to defining what we now refer to as science, but what he called epistêmê, i.e. knowledge. For a detailed analysis of the context and usage of this phrase, as well as alternative phrases that Aristotle uses to describe the same concept throughout his corpus, see Shields, Christopher, “Aristotle”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/aristotle/>.

[16] It is from the translation of the Greek word epistêmê from which the modern English word Science actually derives, through the Latin translation of epistêmê as sciencia.

[17] Falcon, Andrea, “Aristotle on Causality”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2015/entries/aristotle-causality/>.

[18] In Bohm’s terminology, there must be an underlying, or overarching implicate order, which does not rest on these principles and which is a necessary condition, a predicate in fact, to coming to a (more) complete understanding of reality in all its forms and aspects – hence the title of Part IV of this work, On Ontology – a review of the 20th century physicist David Bohm’s work on ontology specifically, his notion of the implicate order, can be found in Part IV of this work.

by Leon Van Kraayenburg

by Leon Van Kraayenburg

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!