The Age of Enlightenment: The Philosophy of Science

Ever since the dawn of civilization mankind has created mythological, semantic and metaphysical paradigms within which the nature of existence and knowledge itself, along with the underlying order of the heavens and the earth and all its creatures within it, mankind included, could be explained. In modern times this evolution of thought, if you can call it that, has culminated in a predominantly deterministic and empiricist view of reality and one which is completely absent of the symbols and psychological import of the act of perception upon this view of reality, a development which can only be looked at as an unintended, and potentially destructive, byproduct of these so-called developments of intellectual progress that were such a marked characteristic of the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment Era in the history of Western civilization. [1]

These altogether Western theo-philosophical developments which have evolved into modern science emerged from the cultural melting pot in the Mediterranean that began first with the Persian and then Greek empires in the first millennium BCE and then was followed by the development and subsequent spread of monotheism by first Latin/Roman imperial conquests and then counteracted and fueled even further by the spread of Islam, forces which ultimately culminated into the revolutionary developments that are so characteristic of the Enlightenment Era period of our history where religion was at best cast aside as a complementary and independent pursuit to knowledge, i.e. science, and at worst was abandoned altogether as a product of the ignorant, uneducated or uninformed mind.

The common thread for Western philosophical development since the teachings of Aristotle however, independent of theological and monotheistic developments which attempted to usurp his, as well as Plato’s teachings, has been the supremacy of Reason and Logic as the tools by which reality and in turn knowledge itself should be defined, the very same tools which were the source for the categorization and development of what we today call science in all its forms, the Tree of Knowledge so to speak. And in modern times, particularly in the last two centuries, this Tree of Knowledge has grown more and more branches as modern man has developed more advanced tools to understand and peer into the universe at both the macrocosmic as well as microcosmic scale and the different branches of science have grown more and more specialized and nuanced.

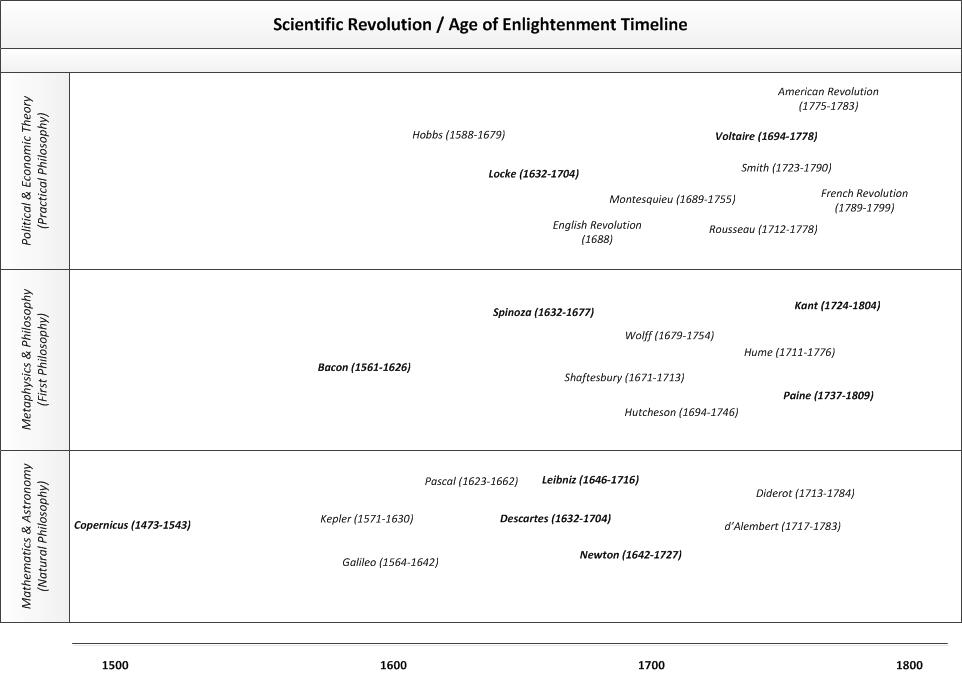

From a pure, or first, philosophical standpoint, i.e. first philosophy, using the definition provided by Aristotle, although many individuals contributed to intellectual developments during what modern historians call the “Age of Enlightenment”, there are four in particular that from this author’s perspective exerted the greatest influence on subsequent modes and arenas of metaphysical thought, all living and writing between the 16th and 18th centuries CE in Western Europe. These are the empiricist Francis Bacon (1561-1626 CE), the famous French philosopher and mathematician Rene Descartes (1632-1704 CE), the Dutch rationalist philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677 CE), and then the great and prolific German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804 CE) whose work in some respects summarizes and consolidates, and represents the height and apex of, Enlightenment Era philosophy.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626 CE) was a successful politician in England the 16th and early 17th century who (re-)established and emphasized inductive methods of inquiry for the attainment of knowledge, providing for the foundations for our modern scientific method which was leveraged not only by subsequent philosophers of the Enlightenment Era, but also by the natural philosophers, or scientists, that followed him that provided the intellectual basis for the Scientific Revolution which followed. Although he was a prolific author and wrote works as broad ranging as political science, ethics, theology and medicine, he is probably best known for his work in natural philosophy and metaphysics than anything else and his attacks on Scholasticism[2] and Aristotelianism in particular as inadequate tools and means for the acquisition and categorization of knowledge, forever changing our approach to how we understand the world around us, how we define reality itself, as well as the means to which we should arrive at such definitions.

Bacon espoused empiricism and inductive reasoning as the most effective means at arriving at knowledge or truth, and speaks from a deterministic and materialistic worldview as laid out by the Epicurean school in classical antiquity, as juxtaposed with the Platonic (and Neo-Platonic) and Peripatetic (Aristotelian) schools which were the primary focus of his (and most other) studies and curriculum that he followed at Trinity College and Cambridge University, both of which followed the “Scholastic” method of teaching that was prevalent at the time. Bacon believed that the human mind was not in fact tabula rasa, or a “clean slate”, and that in order to prepare the individual for the acquisition of true knowledge, it must be purged of what he referred to as intellectual “idols”.

Bacon’s philosophy does not exclude the notion of God or God’s will however, but in order to reconcile the laws of the world of the spirit and the laws of the world of matter, or the material world, he posits the existence of what he refers to as the “Two Books” – the Book of God which he believed reflected God’s Will and the Book of Nature which he believed reflected God’s Works, establishing an intellectual framework within which God could co-exist with science but at the same time splitting the two domains of knowledge into separate pursuits thereby establishing the legitimacy of different ground rules for the acquisition of knowledge in each.

From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Francis Bacon we find a good description of these two different modes of thinking and their relationship to one another:

The glory of God is to conceal a thing, but the glory of the king is to find it out; as if, according to the innocent play of children, the Divine Majesty took delight to hide his works, to the end to have them found out; and as if kings could not obtain a greater honour than to be God’s playfellows in that game, considering the great commandment of wits and means, whereby nothing needeth to be hidden from them.[3]

Rene Descartes (1632-1704 CE) follows shortly after Bacon from an historical perspective and not only establishes the foundations of analytic geometry (the Cartesian coordinate system bears his name), but also makes significant contributions in philosophy and metaphysics proper as well. His seminal work Meditations on First Philosophy[4], provides not only a detailed, rational and logical proof of the existence of God, but also a metaphysical system which incorporated the science of human nature – theology in many respects – alongside the physical sciences. In fact, Descartes’s theory of knowledge, or epistemology, emphasized the importance of mathematics in not only describing reality but in providing the intellectual and metaphysical framework for which things could be “known”.

He is perhaps most famously known for his phrase cogito ergo sum, or “I think therefore I am”, which comes from his work Discourse on the Method and Principles of Philosophy, usually abbreviated as Discourse on Method, signifying the close relationship between perception and existence in his metaphysical framework. Descartes held an Aristotelian view of knowledge, reinforcing the notion that the field of philosophy embodied all knowledge, spanning all of the modern-day disciplines that we now refer to as Science: Medicine, Biology, Psychology, etc. Describing it thus in a letter he wrote to the French Translator of his Principles of Philosophy, using terminology that could just as easily been used by Diogenes Laertius to describe Stoic philosophy in antiquity:

Thus, all Philosophy is like a tree, of which Metaphysics is the root, Physics the trunk, and all the other sciences the branches that grow out of this trunk, which are reduced to three principal, namely, Medicine, Mechanics, and Ethics. By the science of Morals, I understand the highest and most perfect which, presupposing an entire knowledge of the other sciences is the last degree of wisdom.[5]

With Descartes, we find a heavy reliance and emphasis on reason and logic to arrive at truth and knowledge, at a more mature and modernized level than the ancient philosophers that came before him. Descartes the mathematician, as well as the philosopher, attempted to apply the same rigors of inference and deductive reasoning that underpinned the laws of mathematics into the realm of philosophy, metaphysics, and even theology. In his Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes takes his concepts of reason and logic as pillars of truth and understanding to prove the existence of God and the Soul, through the use of the same rational methods that he outlines in his Discourse on Method.

I have always thought that two issues – namely, God and the soul – are chief among those that ought to be demonstrated with the aid of philosophy rather than theology. For although it suffices for us believers to believe by faith that the human soul does not die with the body, and that God exists, certainly no unbelievers seem capable of being persuaded of any religion or even of almost any moral virtue, until these two are first proven to them by natural reason.[6]

One could argue that it is with Descartes that we have firmly established reason and logic in and of themselves as the pillars of knowledge, rejecting the notion of blind faith, or belief, in in things that could not be proved or reasoned out by logic. It is important to point out of course, that while he looked to reason and logic as the cornerstones of all philosophical inquiry, which included first philosophy as well as what we consider today theology, he in no way postulated that God or the Soul did not exist, in fact quite the opposite. He intended to place and prove their existence upon firm, rational and logical foundations. In this context Descartes can be looked upon as an Enlightenment Era Plato of sorts, as Plato very much looked to reason and logic as the primary guideposts of determining the nature of reality just as Descartes did, and they both used these “rational” tools (as Aristotle did thereafter even more so), to attempt to establish not just the reality and eternal existence of ideas in and of themselves (i.e. forms), upon which his principle of the Good ultimately rested, but also the reality and eternal existence of the Soul upon which his entire system of ethics and political philosophy was based. After Descartes and the natural philosophers that followed him, most notably Newton of course, it was almost considered self-evident that the natural universe, material reality, operates according to rational and reasonable laws that are best described by mathematics, the language of God if you will.

Descartes’s intellectual developments in many respects can be looked upon, despite the sophistication of the logic and mathematics that he was exposed to and which clearly influenced his work, as a harkening back to the time of the height of Hellenic philosophy in classical antiquity. A time before theology, as reflected in both the Christian and Muslim movements, dominated the intellectual landscape of Europe and the Middle and Near East for some thousand years or so, a time period referred to by many historians from the Middle Ages even into modern times as the so-called “Dark Ages”, a term used due to of course to the perception that for some one thousand years or so, during the time when religion dominated the intellectual as well as socio-political landscape in the West, pure “scientific” and/or philosophical inquiry independent of religious dogma was almost non-existent.

The next influential philosopher of the Enlightenment Era that made significant contributions uniquely to the intellectual developments of the Scientific Revolution was Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677 CE). Spinoza was a 17th century Dutch philosopher and naturalist of Jewish descent who is perhaps best known for directly and openly challenging the authority of Scripture. He also directly challenged and rejected Descartes’s mind-body dualism, and put forth an alternative metaphysics and moral and ethical framework that is perhaps best described as naturalism, very much in the spirit of the Stoics some thousand years earlier in fact.

Spinoza believed that there was only one corporeal substance that permeated all of nature and that it was governed by a set of rational and universal laws, challenging the notion of Free Will, the existence of an anthropomorphic God, as well as the validity of Scripture and the validity of miracles. His ideas, to say the least, not only constituted very radical notions in his time, but also not surprisingly put him at odds not just with the Church of course, but also within the Jewish community as well. He was excommunicated, or perhaps more accurately put publicly censured, by the Jewish community in 1656, at the ripe age of 23 in fact.

Nature is always the same, and its virtue and power of acting are everywhere one and the same, i.e., the laws and rules of nature, according to which all things happen, and change from one form to another, are always and everywhere the same. So the way of understanding the nature of anything, of whatever kind, must also be the same, viz. through the universal laws and rules of nature.[7]

His seminal work which, was published posthumously, was entitled Ethics and is a systematic critique not just of Descartes’s mind-body dualism, but also of the traditional conceptions of God, and Christian theology in general, along with – as the title implies – and the ethical and moral framework upon which these belief systems sat. Spinoza, as reflected in most predominantly in Ethics but also was a constant theme in his other works as well, advocated – again very much in the same vein as the spirit of the Stoic philosophers some thousand years prior – for the restraint of passions as the key to the leading of a virtuous life which in the end was to Spinoza the true source of happiness. In general, Spinoza promoted and taught that the key to happiness lay in the supremacy of the rational faculty of man over not just blind faith in God or Scripture, but also over the pursuit of passions and desire as well, his philosophy later coming to represent what later philosophers and historians called rationalism.

Spinoza, like many natural scientists that followed him and reflecting in fact a sentiment which is common within the scientific community in modern times – with Einstein being perhaps the most illustrious example – was a determinist and as such believed that all events and effects and outcomes of the world were entirely predestined and based upon the laws of cause and effect, i.e. completely abandoning the notion of Free Will which is incompatible with this doctrine. In his own words, “That eternal and infinite being we call God, or Nature, acts from the same necessity from which he exists.”[8]. His belief in necessity and determinism were hallmarks of his philosophy:

The more this knowledge that things are necessary is concerned with singular things, which we imagine more distinctly and vividly, the greater is this power of the Mind over the affects, as experience itself also testifies. For we see that Sadness over some good which has perished is lessened as soon as the man who has lost it realizes that this good could not, in any way, have been kept. Similarly, we see that [because we regard infancy as a natural and necessary thing], no one pities infants because of their inability to speak, to walk, or to reason, or because they live so many years, as it were, unconscious of themselves. (Vp6s)[9]

As this passage reflects, Spinoza’s answer to the question of how one should conduct one’s life, i.e. his ethical philosophy as it were, was the use of reason itself in order to fully appreciate and understand one’s place in this natural order. In so doing, one can only conclude that one should minimize the extent and influence of the “passions of the human soul” via the pursuit of true knowledge and virtue via reason itself, through which happiness could ultimately be achieved – as much as it could be achieved in the natural order of things that is. Spinoza’s ethical philosophy rests on the principle of the natural world reflecting the unified essence of God, i.e. naturalism, and by subduing those passions that lead to misery, pain and suffering – again the direct cause and effect relationship and the use of pure reason to determine this relationship and reach the conclusion that by removing the original cause the effect, i.e. misery, can also be removed – optimal happiness in this life can be achieved.[10]

This focus on pure reason as the “means to salvation” as it were, and in particular the subduction of the passions as the means by which happiness, i.e. eudaimonia, can be achieved in many respects echoes the sentiments of the Stoic philosophical school from classical Greek antiquity. The idea of suffering and misery being caused by the mindless pursuit of passions, from which one can deduce that by minimizing such pursuits optimal happiness can be achieved, echoes in many respects the Buddhist doctrine of suffering as well. Although there is no evidence that Spinoza was influenced by Buddhist doctrine, it is very possible that the philosophy of the Stoic school influenced him to a large extent

It’s important to recognize however, that even though he disagreed with much of the philosophical framework put forth by Descartes, he nonetheless – like Descartes – did not altogether disavow or reject the notion or existence of “God”, but rather argued that God should be identified with the whole of nature rather than some anthropomorphic and all-knowing deity that sat in Heaven and granted mankind some special place in the universe and on Earth as taught by Christian dogma and Scripture. Hence the naturalist and rationalist categorization of his philosophy which led directly to his expulsion from the Jewish community, and the theological community at large really, given his rejection of Scripture as a source of knowledge and in fact his rejection of the orthodox Judeo-Christian perspective of God.

In Spinoza’s metaphysics God is equated with the underlying substrata of the entire universe and is directly associated with and described as inseparable from Nature, discarding the then orthodox and standard notion of an anthropomorphic omniscient and omnipotent God, and therefore the existence of miracles as a manifestation of his power. He described miracles as “human inventions” and was extremely critical of any literal interpretation of the Bible. Spinoza even went so far in his naturalist bent as to suggest that that human beings, i.e. the race of man, did not hold some special dominion or authority over nature as was espoused by all of the Abrahamic religions, but associated mankind directly with and as a product of Nature, a world which again was governed by wholly deterministic forces and laws that once discovered and properly understood could explain all of the different aspects of reality, including of course how mankind should behave in order to achieve happiness at the individual as well as at the socio-political level.

Spinoza’s represented a sharp contrast to the Christian ideology which had so influenced Europe for so many centuries of course, and it is fair to say that work empowered and emboldened subsequent philosophers and scientists and represented a significant departure from the longstanding Christian (and Islamic and Jewish) theological view that upheld the special place of mankind in the universe. In fact, one can look at Spinoza’s philosophy as laying the intellectual groundwork as it were for the philosophy put forth by the famous English-American political activist and philosopher Thomas Paine (1737 – 1809), one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, who wrote perhaps one of the most influential and controversial treatises of the Enlightenment Era, i.e. The Age of Reason at the end of the 18th century some hundred plus years after Spinoza. Paine, as Spinoza had done before him, strongly rejected the authority of Scripture and the existence of God in the orthodox Judeo-Christian sense, raising the fury of Christian believers on both sides of the Atlantic but at the same time no doubt influencing the design of the Constitution of the United States with its fundamental separation between Church and State.

On the natural philosophical side of development, the branch of the Tree of Knowledge that ends up transforming into what we today refer to as the Science proper, the beginning of the Scientific Revolution starts with Copernicus (1473-1543), best known of course for explicitly challenging the long held belief that the Earth was the center of the Universe, a notion that underpinned Western civilization’s view of mankind’s place in the cosmos for at least a thousand years and was a cornerstone to Christian theology.[11] The association between Astronomy/astrology and Religion had a long tradition dating back to the dawn of Western civilization, reflected in the belief systems of the Ancient Babylonians, the Ancient Egyptians, and of course the Ancient Greeks and Romans. It was with Copernicus however that the break between these two disciplines, religion and Astronomy, was rifted for good however, solidified over the centuries following Copernicus with the work of Galileo, Kepler and then Newton, all who built upon and confirmed Copernicus’s thesis of heliocentrism and established the foundations of modern Astronomy, and science in general in fact, as well as its close association with mathematics.

As previously noted, the curriculum that was taught throughout the institutions of higher learning throughout the Middle Ages and into the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries was greatly influenced by the Church and its institutions of learning which were run primarily by monks and priests, all of whom taught (and presumably believed) that mankind was created by God in his own image and that the Earth, which mankind held dominion over by divine authority, was the center of the Universe. When Copernicus questioned this assumption, based primarily upon mathematical problems he encountered in Ptolemy’s work, the Church did not receive this criticism lightly to say the least.

Copernicus most influential work which laid out his case for a heliocentric model of the universe was written in Latin, as most standard intellectual works of his day were, and was entitled De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, or On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, sometimes referred to simply as On the Revolutions. It was published just before his death in 1543 and set out to demonstrate that the observed motions of stars, planets and other celestial bodies can be explained without having the Earth be the center upon which all else revolves. It being published posthumously kept Copernicus out of controversy for the most part, but as is work was picked up and expounded upon by subsequent authors and teachers, most notably Galileo, the rift with the Church manifested quite forcefully.

Galileo (1564-1642), sometimes referred to as the “father of science”, was the first to publicly defend Copernicus’s thesis that the Earth revolved around the sun, despite Copernicus’s On the Revolutions being officially condemned pending correction in 1616 some 60 years after it was published. Galileo defended the Copernican system in his work, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, a work which was published in 1632 in Italian and translated into Latin in 1635 and compared the Copernican and Ptolemaic systems directly and laid out a strong case for a heliocentric model of the universe. In 1633, in no small measure due to his popularity, Galileo was condemned by the Church, convicted of heresy, forced to recant his heliocentric views, and exiled, spending the rest of his life under house arrest where he ironically produced perhaps his most profound work, Discourses Concerning the Two New Sciences which was published (in Italian) in 1638. In the Two New Sciences, Galileo outlined an entirely new framework for natural philosophy, described two new fields of study that fell under the heading of natural philosophy which he called “strength of materials” and “motion of objects”, laying the groundwork for the field of Physics which was to follow in his wake.

In the Two New Sciences Galileo lays the foundation for the work of Kepler and Newton among others and provides the intellectual framework within which modern Physics sits, where celestial and terrestrial matter obey the same laws and where the language of mathematics is called out specifically to be the greatest form of universal expression.

For most people, in the 17th Century as well as today, Galileo was and is seen as the ‘hero’ of modern science. Galileo discovered many things: with his telescope, he first saw the moons of Jupiter and the mountains on the Moon; he determined the parabolic path of projectiles and calculated the law of free fall on the basis of experiment. He is known for defending and making popular the Copernican system, using the telescope to examine the heavens, inventing the microscope, dropping stones from towers and masts, playing with pendula and clocks, being the first ‘real’ experimental scientist, advocating the relativity of motion, and creating a mathematical physics. His major claim to fame probably comes from his trial by the Catholic Inquisition and his purported role as heroic rational, modern man in the subsequent history of the ‘warfare’ between science and religion. This is no small set of accomplishments for one 17th Century Italian, who was the son of a court musician and who left the University of Pisa without a degree.[12]

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) was a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer, and although a contemporary of sorts of Galileo, followed in his footsteps and built off of Galileo and Copernicus’s work to invent (or discover depending upon your perspective) three laws of planetary motion around the sun, grounding Copernican heliocentrism in sound mathematics and laying the groundwork for Newton’s theory of universal gravitation.[13]

Throughout the Enlightenment Era period, consistent widely held beliefs since the dawn of civilization, there was no hard line drawn between Astronomy and astrology, although there was a strong division since Aristotle between Astronomy, which was typically covered in mathematics, and Physics, which was considered a branch of natural philosophy and covered separate from Astronomy. Kepler’s work, built off the foundations laid out by Galileo before him, broke down the distinctions of these two fields however and created an even larger divide between theology and science, where Astronomy became a subsidiary branch of natural philosophy and was governed by the same laws as the physical world, i.e. the field of natural philosophy. Kepler however, consistent with the philosophers that preceded him, did not abandon Religion altogether but encapsulated theology and the belief in an anthropomorphic Creator in his works, arguing that mathematics, reason and logic, were the tools used by God to create and maintain the universe, further entrenching rationalism and empiricism into the intellectual development that followed him and further galvanizing Religion and Science.

It’s with Newton (1642-172) however that we see celestial and terrestrial mechanics become completely integrated in a holistic system as well as the solidification of mathematics as the tool best suited to describe God’s creation. Newton, best known for his principle of universal gravitation which underlies his three laws of motion which govern the interaction of all mass and bodies in the universe, provided the final blow to the Ptolemaic/Aristotelian (and Christian) geocentric model of the universe. His work was the final blow to the Judeo-Christian view of the universe as God’s willful creation and marks the rise to supremacy of the role of mathematics and scientific method in the description of the “physical” world. Newtonian Mechanics, as it is commonly referred to today, dominated the scientific view of the universe for the next three centuries and arguably still represents the primary mode within which most of us understand our relationship to the physical world around us even today[14].

What is most fascinating about Newton though, when you looked under the covers a bit and tried to step back from the laws of physical motion that he was most known for, was that he was an interesting and diverse, and god fearing, intellectual with a wide range of interests in a variety of fields, both scientific and theological. For example, in his astronomical studies he invented the first reflecting telescope and in the field of optics he was the first to demonstrate that light can be decomposed into a spectrum of colors via a prism. He is also known for his contributions to the field of mathematics of course, with the invention of calculus in particular[15], but he also was a serious student of alchemy and some scholars and historians even believe that it was his work with alchemy in particular that provided Newton with the inspiration for his notion of gravity.[16] John Maynard Keynes, the famous economist, after purchasing many of Newton’s extant alchemical treatises, is reported to have said, “Newton was not the first of the age of reason, he was the last of the magicians.”

But Newton, as with his predecessors, did not abandon faith in God. Although he was unable to accept the beliefs of the Church of England (and according to some scholars believed that the Church had deviated from the teachings of Christ over the centuries), he was required as a Fellow of Trinity College to take holy orders, i.e. follow the curriculum and guidance of the Church with respect to what he could research, write about or teach. The Church of England however, was more understanding and sympathetic to the ideas of Newton than Galileo, and King Charles II issued a royal decree excusing Newton from the necessity of taking holy orders saving Newton from the hardships and censorship that Galileo had to endure.[17]

What is interesting then in looking at the life of Newton rather than focusing on his scientific discoveries, and considering all of his works and contributions to many different branches of thought, was that Newton must have had a very broad view of the nature of the universe that synthesized what we might consider to be mystical or theological in today’s nomenclature with his belief in the natural order of the universe which was best described in mathematical terms. Like many of the other Enlightenment Era philosophers and astronomers that preceded him, Newton clearly believed that there existed fundamental laws which governed the material universe, laws which were best described by mathematical equations and relationships. Laws which could be arrived at by inspiration (the establishment of a premise or hypothesis), but needed to be verified empirically, i.e. proven, via experimentation and measurement to validate these theories.

However, to look at the conclusions that Newton came to with respect to the world of classical mechanics without at least taking note of his theological beliefs and his considerable work in alchemy (much of which was apparently lost in a fire), would be like tasting a salad without dressing – yes it would be the same salad without the dressing, the same underlying physical and chemical structure of lettuce fruits and vegetables, but it would lack flavor, and all of the subtleties and intricacies of the taste of that very same salad with the dressing. And it’s Newton’s alchemical, theological and philosophical beliefs that were the dressing to the salad of his work in Classical Mechanics and mathematics, a fact which has very much been lost with respect to his contributions to Science as they are presented to students today.

During the Enlightenment, the supremacy of rationalism and empiricism became firmly established in the intellectual community no doubt, but the rational order of the universe as a divine emanation of an anthropomorphic God was still very much present in the works of the great philosophers and (what we would today call) scientists of the Age of Reason, despite their view that reason and empiricism was to be held in the highest regard and the one and only tool for enlightenment and knowledge – higher than revelation, scripture or even faith in God itself. While not a bad thing in and of itself, particularly given how those in power had abused religion over the centuries to serve the pursuit of power and authority of the few over the many, of the fortunate over the unfortunate, this very same emergence of Science during the Enlightenment Era period sowed the seeds of this mechanistic and deterministic worldview which characterizes the modern Western world, a view where belief in the existence and importance of the Soul as the source of ethics and morality was subsumed by the belief in the rule of law and the powers of free market economy and capitalism as the source of welfare for society.

As a result of these developments however, advancements that have improved society and social welfare no doubt, expanding the average lifespan of the individual by a factor of two or three at least, we now live in a world that is dominated by materialism, a world where the notion of what reality is can only be determined only by the use of deductive reason based upon that which can be proven to exist by the observation of undeniable facts that consist of that which we can see, touch or hear or smell by either direct perception or via technologies that enhance these powers of perception, and one which presumes that the entire universe, including the evolution of mankind along with all of the biological processes which are such a marked characteristic of life itself, must be governed by fundamental laws of cause and effect which have either already been discovered or have yet to be discovered.

This revolution that brought about the developments of the Scientific Revolution during the period which modern historians call the “Age of Reason” was a direct result of the spread of Abrahamic monotheism from the time of the Roman Empire up through the Middle/Dark Ages where theological and philosophical views were imposed upon people by force and by legal mandate and where religious ideology was usurped to consolidate and expand the power and authority of the fortunate few over the unfortunate and uneducated masses. These imperial rulers and the aristocracies and armies that supported them imposed their versions of theology upon the masses, using religion and “salvation” as justification to quench their thirst for more power and more riches and expand their empires, leading to systems of belief that were devoid of any rational moral or ethical framework beyond the avoidance of damnation in eternal fiery Hell, absent of the rational systems of ethics and morality that had been emphasized and put forth by the philosophical schools of Ancient Greece which rested on the fundamental belief in the Soul and virtue, or excellence, as the highest pursuit of man.

As the true import and unadulterated teachings of the Greek philosophers proliferated during the Enlightenment Era, handed down by the Greek scholars and philosophers and subsequently kept alive by the intellectual communities of first the Latin/Romans which espoused Neo-Platonism and then by Arab intellectuals, falṣafa, in the Middle Ages who translated and interpreted these ancient works into Arabic, these faith based and rationally bereft Abrahamic religious doctrines which had played such a prominent role in the development of Western civilizations for some 1500 years were supplanted by what can only be termed radical developments in socio-political theory, natural philosophy and metaphysics all of which in toto make up what modern historians refer to as the Enlightenment Era. And the Scientific Revolution which was a key factor in driving these Enlightenment Era developments throughout Europe and the Western world, with all the benefits and technological progress which it drove, represented the first nail in the coffin of the subjugation of the reality of the Soul to the reality and supremacy of the material world, laying the foundations for the materialistic and mechanistic view of reality which is endemic in Western society today.

[1] The Scientific Revolution is an historical period which is classically bound by modern historians by Copernicus’s publication of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) in 1543 and ends with Newton’s publication of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) in 1687.

[2] Scholasticism is a method of teaching and learning that dominated the intellectual landscape in universities during the “Medieval” period of history in Europe from circa 1100 to 1700 CE. Scholastic method placed a strong emphasis on dialectical reasoning, which included inductive as well as deductive methods of logic as elucidated primarily by Aristotle in classical antiquity, as the basis for knowledge and the establishment of truth versus falsehood. Reconciliation and harmonization of Christian theology and classical philosophy, which included the sciences as we understand them today, was one of the main thrusts of the curriculum in general. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Scholasticism’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 23 November 2016, 00:51 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Scholasticism&oldid=751042398> [accessed 23 November 2016].

[3] Taken from Klein, Jürgen, “Francis Bacon”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2012/entries/francis-bacon/>. Quote from Blumenberg, Der Prozess der theoretischen Neugierde, 1973. For more on Bacon’s philosophy and theory of Idols and theory of Two Books, see http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/.

[4] Meditations on First Philosophy was originally written in Latin and first published in 1641, its title revealing the still prevailing influence of Aristotle on the various branches of knowledge, i.e. first philosophy being equivalent to metaphysics as it were and in Medieval times, as in antiquity although to a lesser extent, represented the inquiry into the fundamental nature of existence, i.e. metaphysics and/or theology depending upon the emphasis of the tradition within which it was studied.

[5] René Descartes: Letter of the Author to the French Translator of the Principles of Philosophy serving for a preface”. Retrieved December 2011.

[6] Meditations on First Philosophy, Rene Descartes, Third Edition, Letter of Dedication, pg. 1.

[7] Nadler, Steven, “Baruch Spinoza”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2012/entries/spinoza/>. Page 22.

[8] Spinoza, Ethics, Latin version only. Part IV, Preface.

[9] Nadler, Steven, “Baruch Spinoza”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2012/entries/spinoza/>. Page 27.

[10]. See the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Spinoza for parallels on his philosophy with some of the Greco-Roman Stoic philosophers from antiquity – Nadler, Steven, “Baruch Spinoza”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2012/entries/spinoza/>.

[11] Although there had been authors and mathematicians that had proposed a heliocentric view of the universe in late antiquity, most notably by Aristarchus in the 3rd century BCE and then Seleucus of the 2nd century BCE, it was the geocentric models expounded by Plato and Aristotle, codified in Ptolemy’s Almagest in the 2nd century CE, that served as the standard astronomical textbook throughout the Middle Ages up until Copernicus challenged its fundamental assertions and underlying mathematics.

[12] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University, Galileo Galilei, by Peter Machamer.

[13] Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion specifically are 1) the orbit of each planet is elliptical with the sun being one of the two foci of the ellipse, 2) a line joining each planet and the sun sweeps out along the elliptical orbit in equal areas during equal intervals of time, and 3) the square of the orbital period of a planet is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kepler/ for a more full account of the mathematics underlying his laws.

[14] Newton’s three laws and principle of universal gravitation are laid out in Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, published in Latin in 1687. For a more detailed account of the Life and Works off Isaac Newton see https://snowconesdiaries.com/2012/10/21/classical-mechanics-the-life-and-times-of-sir-isaac-newton/ by the same author.

[15] Leibniz also invented calculus at around the same time somewhat independently as well. For a history of calculus and specifically the controversy surrounding its discovery between Newton and Leibniz see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_calculus.

[16] Alchemy is an ancient philosophical tradition stemming from the doctrines attributed to Hermes Trismegistus (Corpus Hermeticum) that transformed in Medieval times from its philosophical roots to more materialistic pursuits, including the creation of the fabled philosopher’s stone which could facilitate the transformation of base metals into gold or silver. The practice still has a following even today, even though it is a very small one, and its philosophy from a psychological and spiritual perspective had a profound influence on Carl Jung..

[17] More specifically the decree specified that, in perpetuity, the Lucasian professor, which was the title given to the incumbent of the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge (widely regarded as one of the world’s most prestigious academic posts even to this day, currently held by the famed theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking), was exempt from holy orders.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!