The Legacy of Socrates: Skepticism, Knowledge and Reason

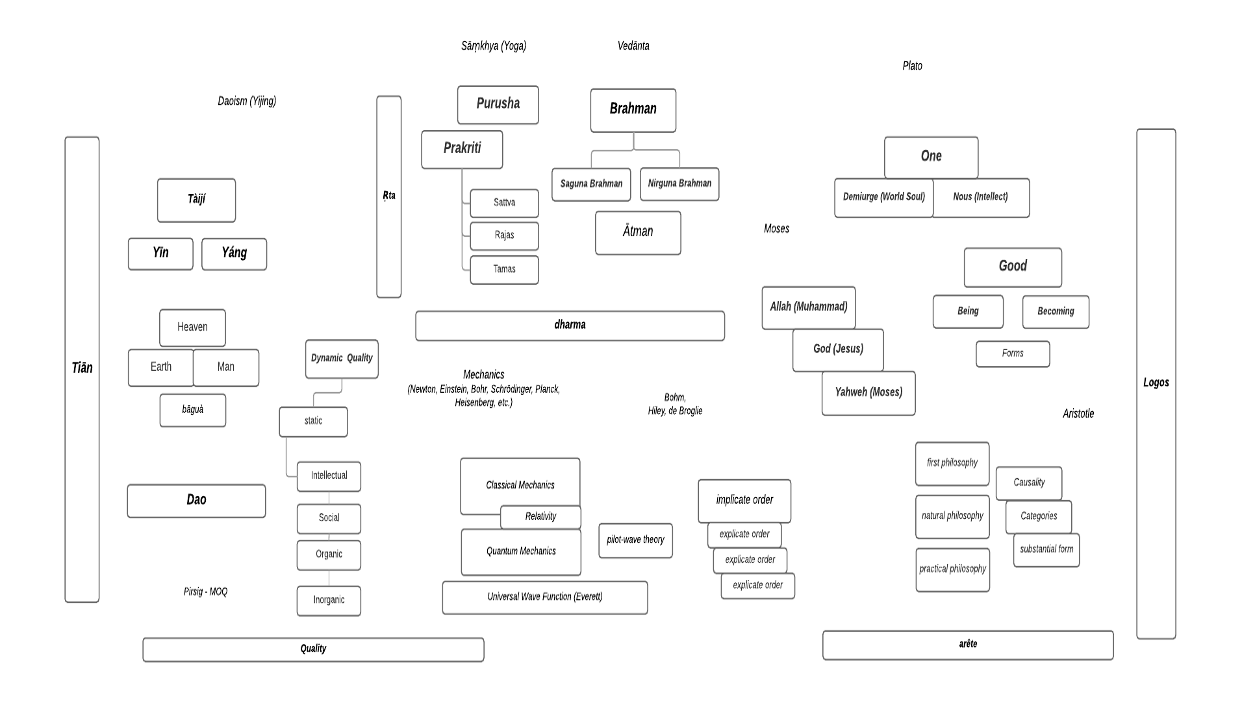

One of the best indications of the influence of Socrates on the development of Western philosophy, what the Hellenes, or Greeks, termed philosophia, his ideas being primarily represented by the writings of his best known pupil Plato, is the more modern delineation of philosophical systems into Pre-Socratic philosophy to the philosophical and metaphysical systems of belief that came after Plato, marked most notably by Aristotelianism and Neo-Platonism among other philosophical systems. In other words, in terms of the evolution of what the ancients termed “philosophy”, which provides the basis for all of the branches of knowledge that today we would categorize as Science, Biology, Ethics, Social Science or Political Philosophy, and even Psychology, current historians and scholars basically divide philosophical history into Pre-Socratic, Platonic, and Aristotelian, and then virtually everything that came after them as represented by the works of Aquinas, Descartes, Kant, and Newton among others.

Socrates (469 – 399 BCE) was born in Athens circa 470 BCE to a modest family but consistent with all Athenian males in the 5th century BCE however, he was given an education and taught to read and write, and was required to serve the city in various public and military faculties. Before his days as a wandering philosopher in Athens, Socrates is known to have served valiantly in the Athenian military, having fought bravely in several battles against the Spartans during the Peloponnesian War (431 – 404 BCE). It is said that in the battle of Potidaea (432 BCE) for example, he saved the life of the famed Athenian general Alcibiades, with whom he is said to have had a very close relationship with (and perhaps was even romantically involved with) and through which his association contributed to his being put to death by the Athenian state in 399 BCE.[1]

Although Socrates (471 – 399 BCE) did not author any works himself, his teachings and many of the details surrounding his death do survive in the accounts and writings of his students, most notably Plato (428 – 348 BCE) of course, but also Xenophon (431 – 354 BCE), as well as in indirect accounts and references in the works of other semi contemporary Greek authors such as the Greek satirical playwright Aristophanes (445 – 385 BCE) [2]. Socrates life’s end is marked by his execution by Greek authorities for, at least according to Plato, corrupting the minds of youth and challenging the legitimacy of the gods as well as the established authority of the aristocracy of Greek society of the day. Both Plato and Xenophon wrote works describing the last days of Socrates and the trial specifically, where Socrates attempts to defend his position as simply a seeker of wisdom and man of virtue, almost enticing his accusers to sentence him to death rather than banish him to some foreign land.[3]

Socrates then personifies what we conceive of today as the prototypical classical philosopher, despite the contributions of the intellectuals and thinkers that came before him. However, what the ancients considered philosophy and what we consider philosophy today, and in turn metaphysics which was a term first used by Aristotle (meaning literally “after” or “beyond” indicating that Metaphysics should be studied after Physics), are conceptually similar but at the same time very different things. The ancient Greeks devised and understood the term philosophy, the first use of which is attested and attributed to Pythagoras, covered a much broader range of topics and branches of thought than the modern conception of the term.

Plato’s works, in particular his earlier works, are written in a form of literary prose referred to as Socratic Dialogue, named as such not only due to the fact that Socrates is a prominent character and voice of the philosophical tenets which Plato’s puts forth, but also due to the fact that it is typically assumed, particularly with respect to his earlier dialogues, that the philosophical positions that he argues for are presumed to have originated with Socrates himself.[4] But outside of second hand accounts, we have no direct works from Socrates so for the most part we know of Socrates and his philosophical beliefs and metaphysics through the words of Plato. These are important backdrop and contextual items that must be kept in mind when looking at Plato’s works and discerning what his “philosophy” truly was, and how much of it was his interpretation of Socrates and how much of it was his own workings and reformulations of the teachings which he presumably received from Socrates himself.

It must be kept in mind, when looking at and reviewing the authors of Plato and Xenophon in particular who both wrote what are considered to be direct accounts of the last days of Socrates, that the political backdrop was a time of war, a war that affected the entire Greek realm at the time. The Peloponnesian War was the great conflict between Athens and her empire and the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta at the end of the 5th century BC (431 to 401 BC), the termination of which marked the end of the golden age of Athens, after the loss of which was relegated to a secondary city-state in the classical antiquity.

This conflict raised many questions as to the nature of political systems in general to the great thinkers of the day, as Sparta’s form of government differed in many respects to that of Athens, and given the war that had such a significant impact on all of Ancient Greece and its bordering city-states at the time, much of the philosophical works of Plato, as well as Aristotle in fact, analyzed the competing socio-political systems of the day and proffered up opinions, philosophical and otherwise, upon which system of government was the best. It was from this socio-political self-analysis and introspection, stemming from the great perils and destructive force of war, that democracy in its current form was forged.

Therefore, the role of the state, the exploration into the ideal form of government, and the role of the philosopher within the state, topics that would not be classically consider as philosophical inquiries today, are in fact the main themes that run through Plato’s Republic, arguably one of his most lasting and prolific works. In this text, Plato explores the various forms of government prevalent in ancient Greek society and specifically delves not into the meaning of justice and virtue (arête). He also, through the narrative of Socrates, explores the role of the philosopher in society, even going so far as to speak of the utopian form of government being one that is led by the “philosopher-king”.[5]

In a broader sense, The Republic portrays Socrates, along with other various members of the Athenian and foreign elite, discussing the meaning of excellence or virtue, i.e. arête, within a socio-political context, examining whether or not the just man is happier than the unjust man by comparing and contrasting existing regimes and political systems, as well as discussing the role of the philosopher in society. All of these themes must have crystallized in Plato’s mind and life after the death of his beloved teacher Socrates given the socio-political context within which he was put to death. Plato’s concern with the ideal city-state, reflected in the title of the work that was given to it by later historians and compilers of his work on this topic, i.e. Republic, focused on the value and strengths and weaknesses of democracy as it existed in Athens, again an important topic of the day given the broad impact of the Peloponnesian War on the world of ancient Greece at the time and the competing forms of government each side of the conflict espoused.

Another example of the importance of the state in the early philosophical works of the ancient Greeks comes from Aristotle’s Politics. Here Aristotle continues Plato’s exploration into various forms of government and their pros and cons, looking specifically at the government of Sparta in one passage, describing it as some combination of monarchy, oligarchy and public assembly/senate of sorts, all of which were combined to balance power, in many respects similar to the balance of power as reflected in the House, the Senate and the office of the President in the United States today.

Some, indeed, say that the best constitution is a combination of all existing forms, and they praise the Lacedaemonian [Spartan] because it is made up of oligarchy, monarchy, and democracy, the king forming the monarchy, and the council of elders the oligarchy while the democratic element is represented by the Ephors; for the Ephors are selected from the people. Others, however, declare the Ephoralty to be a tyranny, and find the element of democracy in the common meals and in the habits of daily life. At Lacedaemon, for instance, the Ephors determine suits about contracts, which they distribute among themselves, while the elders are judges of homicide, and other causes are decided by other magistrates.[6]

So government then, its role and purpose, as well as the role of the individual citizen, were clearly very important topics of the early Greek philosophers and you’d be hard pressed to believe that to at least some extent they influenced the development of various political systems in their day. But their most lasting contribution arguably was their devotion to the pursuit of knowledge and truth for their own sake, as opposed to the pursuit of knowledge to establish the legitimacy of authority and the ruling class which had been the pattern that had existed for centuries if not millennia before them, as well as their creation of institutions of learning from which this new field of study could be practiced and taught, passing its tenets down to later generations not only orally but through a written tradition for further enquiry and analysis by subsequent students, as reflected in the works of Plato and Aristotle which survive to this day.

While the philosophical doctrines of Socrates are believed to be reflected in Plato’s earlier works and the philosophy of Plato himself are gleaned from his Middle and Late dialogues, the works of his most prolific student Aristotle explored topics and subjects which we today would consider fall under the category of Philosophy, but also covered topics such as theology, ethics, the underlying principles of logic and reason (dialectic), as well as what we today would call metaphysics, or the study of the nature of reality and knowledge itself. All of these topics fell under what the ancients termed philosophy, what the Greeks termed philosophia, or more specifically what Aristotle referred to as epistêmê, which is typically translated as “sciences” but is the plural of the Greek word for “knowledge”.

Plato was by far the most prominent of Socrates’s disciples and was a prolific author, all of his writings however coming after the death of his mentor and therefore at best represent at least one generation removed of the actual life and times of the great martyr who as the story goes sacrificed his life in the name of truth and knowledge. Plato lived and wrote in the latter part of the 4th and early part of the third century BC (circa 424 to 327 BC), and in his later life founded the Academy of Athens, the first known institution of higher learning in the Western world that persisted until the beginning of the first century BCE, the same Academy from which Aristotle was schooled. Thirty-six dialogues have been ascribed to Plato, and they cover a range of topics such as love, virtue, ethics, and the role of the philosopher in society.

Plato however is named specifically in the Apology as being present at the day of Socrates’s the trial however, as well as is called out in the Phaedo as being one of the close followers of Socrates who could not make it on the day of his execution because he was ill, so it is safe to say that a very close relationship existed – at least from Plato’s perspective – between Plato and Socrates and that perhaps some of the depictions of Socrates by Plato in his dialogues are representative of first-hand accounts so to speak. However, taken as a whole though, what we know of Socrates – from whose example and teachings clearly greatly influenced Plato who in turn was the teacher of Aristotle, arguably two of the most influential Western philosophers of all time – as understood through the words of Plato at least, must be looked at least somewhat skeptically for it is surely through rose colored glasses, through the writings of Plato and Xenophanes in particular, that he historical figure of Socrates is known by the modern reader and scholar primarily.

While little is known of Plato’s early life according it is believed that he was born to a wealthy aristocratic family in Greece on the island of Aegina just south of Athens toward the end of the 5th century BCE (428/427 BCE). As most aristocratic Athenian youth he was well educated and according to Diogenes Laertius he was instructed in the arts of grammar (reading and writing), music, painting and gymnastics and, not surprisingly, was a very good student. It is also held that he excelled as a wrestler and that he competed, and did well, in the Isthmian Games, one of the Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece that was held on off years of the famed Olympic Games.[7] His introduction to philosophy supposedly started as a student of Cratylus, a student and follower of Heraclitus and was also a prominent figure, and title, of one of Plato’s middle dialogues.[8]

It is commonly assumed that the doctrines and philosophical positions that Plato puts forth in his dialogues, particular from his Middle and Late Period, represent his philosophical position more or less, and many of the characters and (alternative) points of view and positions that are explored in his dialogues represent at least to some degree the varying philosophical positions and views that were prevalent by the various teachers and intellectuals contemporaries or predecessors of the era within which Plato wrote. For example, Anaxagoras, Parmenides, and Cratylus. are all characters in his dialogues that are used as foils within his works to represent, and ultimately refute, their various philosophical tenets and systems of belief. Furthermore, it is believed that in almost all cases Plato’s views and positions are presented through the character of Socrates, who is a prominent figure in virtually all of Plato’s dialogues and is the voice through which Plato expresses his philosophical views, along with the arguments and reasons (logos) to back up his positions.

Plato’s intention then, no doubt inspired by his teacher Socrates who was sentenced to death for “impiety”, or questioning the reality of the old gods and traditions which were such an important part of the Greek culture and society, was not necessarily to reject the old traditions outright, but certainly to question them and place them within a more rational and coherent intellectual framework, a framework which still reflected an underlying belief and faith in the gods and mythology of prehistoric man, but attempted to distinguish between faith and knowledge (science), and provide more rational underpinnings for morality and ethics as a whole, and even systems of government to which we still owe him a great debt.

With respect to the modern interpretation of the evolution of Plato’s philosophy, modern scholars typically divide Plato’s works, his dialogues (so called due to the style of prose that Plato used throughout, a conversational like setting between two or more characters) into three categories – Early, Middle and Late. His Early dialogues, are presumed to reflect the teachings of Socrates and primarily deal with ethics, morality and the leading of a “good” and virtuous life. These include the Charmides, Crito, Euthydemus, Euthyphro, Gorgias, Hippias Major, Hippias Minor, Ion, Laches, Lysis, and Protagoras. His Middle dialogues, or dialogues from his “Middle period”, which are best represented by the Phaedo, Cratylus, Symposium, Republic, and Phaedrus are believed to represent Plato’s first foray into the exploration of his own philosophical doctrines, primarily constructed upon his theory of forms.[9]

His later works, representing the most mature state of his philosophy and the most elaborate and stylistic of language are the Sophist, Statesman, the Timaeus, Critias, Philebus, and what is believed to be his last work, Laws.[10] It is in this Middle Period that we see Plato develop his predominantly idealistic views on the nature of reality, the ontological precedence of ideas over matter upon which his theory of forms ultimately rests, and upon which he posited the fundamental reality of ethics and virtue as eternally existent “things” in and of themselves, i.e. forms, and in turn the role of dialectic and reasoning (logos) in establishing their “reality”, reality in the sense that they were not subject to change. It is from the philosophical development as reflected in his works in this Middle Period that Plato establishes the rational ground for the eternal truths of virtue, ethics and ultimately the Good, and then in perhaps his most famous and influential work the Republic where he describes the importance of the role of philosophy and in turn the philosopher, i.e. he who pursued wisdom, i.e. sophia, for its own sake, on the structure of the ideal state.

All of Plato’s dialogues were exactly that, the documentation and exploration of various ideas and topics as love, friendship, virtue, morality etc., via conversation and argumentation between two or more characters where these various ideas, what came to represent Plato’s “philosophy” were approached and described from various intellectual points of view in order to arrive at some sense of truth or essence of the topic at hand. His dialogues are typically structured as conversations between two or more persons where basic hypothesis or theories are put forth and then in turn criticized followed by the related defense of said theories, with Socrates being the predominant figure in virtually all of his works. This form of reasoning, for which Plato is perhaps best known for, came to be known as dialectic, i.e. the exploration of theoretical and metaphysical concepts by the use of a narrative or dialogue between various (fictitious or historical) characters, where various philosophical principles.

The format that Plato uses throughout all of his works is one of the presentation of differing points of view of an argument by various characters in his dialogues in order to explore, and ultimately conclude, various philosophical points. The common thread throughout these dialogues is the supremacy of reason, the use of logic and argument (dialectic), to establish various points of view as well as basic philosophical and metaphysical positions, upon which what we know today as Platonic philosophy is presented to the modern reader. This unique characteristic of Plato’s writings, the format within which he explores and presents his ideas, in and of itself had lasting effects on the development of Western thought, and teaching of philosophy in general, that lasted well throughout the middle ages, continuing to be used as the means of teaching to a greater or lesser extent as it evolved into its more modern form which came to be known as Scholasticism which was used as the teaching methodology for many of the earliest universities that cropped from the 11th century onwards up through the Enlightenment Era.

While Socrates plays a significant role in many of Plato’s dialogues, and although it’s not clear to what extent the narratives that Plato speaks of are historically accurate, Plato does make use of a variety of names, places and events in his dialogues attributed specifically to Socrates and others that lend his dialogues a sense of authenticity, be they historically accurate or not[11]. So although it is safe to assume that the life and teachings of Socrates formed much of the basis of many of the philosophical constructs that Plato covers in his extant work, particularly in his Early dialogues, just as in the analysis of any ancient literature or culture, the historical and political context within which the works were authored must be considered when trying to determine their import and message.

Taken as a whole however, given the philosophical and metaphysical nature of the topics Plato explores in his extant work, historical accuracy isn’t necessarily an imperative for him. In other words, Plato is not attempting to provide any sort of historical narrative but attempting to lay out alternative points of view on a variety of topics to yield knowledge and truth regarding esoteric topics that had hitherto been unexplored. In other words, given the purpose of Plato’s dialogues and extant work, the veracity of the individual beliefs of the persona in his dialogues, or even the accuracy of events which he describes, are of less importance and relevance than the topics which he discusses as well as the means by which he explores the topics – namely dialectic or dialogue form.

It can be argued however that Plato believed, and this view was inherited to a certain degree by Aristotle, that the most direct and powerful way to arrive at truth or the essence of an abstract topic was through dialogue or argument, and so almost of all of his writings were drafted in this form. From Plato’s perspective, it was only through dialectic, through the bantering and discussion of varying points of view by several individuals, that the truth or wisdom of a certain topic could be revealed – if in fact the true nature of Truth on the topic at hand could indeed actually be established, hence the skeptic nature of many of the later interpreters of his work. This form of writing and exposition by Plato can be viewed as evidence of Plato’s insistence that pure, absolute truth is unknowable, but can be explored or better understood by evaluating all sides of an issue or topic and using reason and logic to arrive at understanding, even if absolute truth is elusive.

But again, when trying to discern or determine “Plato’s philosophy”, or Platonism, in its early stages as it is sometimes referred to, it is important to remember that perhaps Plato’s most lasting contribution to Western thought was not necessarily the philosophy that he presented, the one which he assume he learned from Socrates, but the means by which he presented and explored these philosophical principles – through dialogue and debate, i.e. dialectic – a method which was much more profound and lasting in and of itself than the doctrines and belief systems that we infer to be contained or found in Plato’s works and a method which rested on the supremacy of reason, i.e. logos, and argument and logic to a great extent, over myth or blind faith. A constant theme in all of Plato’s dialogues then is the method of teaching itself, a method which spoke to the power of the mental faculty of man more so than any of his predecessors, predecessors which had for the most part relied on poetry and mythology as tools of exposition and explanation (and to some extent even mysticism in the sense of direct divine revelation and the absence of reason or logic from which poetry can be seen to have derived) and the establishment of truth.[12]

[1] Alcibiades was an enigmatic Athenian political and military figure toward the end of the 5th century BCE and at various stages, for a variety of political reasons, allied himself not only to Sparta, but also to Persia, the two greatest enemies of the Athenian democratic state. After the Athenians lost the war to Sparta in 404 BCE, the Spartans put the rulership of the city in the hands of a small group of Athenian citizens that were known to be loyal to Spartan interests, what came to be known as “The Thirty”, or the “Thirty Tyrants”, who mercilessly executed and confiscated the property of a number of aristocratic Athenians who were democratic sympathizers. The Thirty were overthrown by Athenian democratic supporters just one year later in 403 BCE by a group of Athenian democratic supporters from exile. Alcibiades however, given his known affiliations with Persia and Sparta, as well as his association with the defamation of the statues of Hermes in Sicily in 415 BCE as well as his implication in crimes against the Eleusinian Mysteries, was no friend of the Athenian state by the time the era of Spartan influence came to an end. By the time of Socrates’s trial for “impiety” and the “corruption of the youth” in 399 BCE, his relationship with Alcibiades is believed to have contributed considerably to his demise. See Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Socrates. By James M. Ambury, King’s College. http://www.iep.utm.edu/socrates/#H1

[2] Socrates plays a significant role in Aristophanes Clouds, a satirical play of the sophist and philosophical traditions of late 5th century BC Athens. He is primarily depicted as a bit of a buffoon in the play, but if nothing else it reflects the broad cultural and socio-political impact that the philosophical and sophist traditions of his day, Socrates and Plato reflecting the most prominent schools, and therefore the easiest targets to be made light of.

[3] Plato was present at Socrates’s final hearings of judgment, as we find in the Apology, which is Plato’s account of the Socrates’s defense which he lays out to his Athenian council members where he stands accused of “corrupting the youth and of not believing in the gods of the Athenian state”, a crime punishable by death apparently to which Socrates willingly accepts. His reasoning for the acceptance of this judgment is related in the Crito which is an account of a conversation between Socrates and Crito while Socrates awaits his death sentence in his cell which covers the topics of justice and injustice among other things.

[4] Socratic Dialogue is not to be confused with Socratic method. The former refers to a style of prose that characterizes many of the philosophical works of both Plato and Xenophon, both of whom were students of Socrates. The latter refers to a (literary) method of argument that while also associated with the majority of Plato’s works, refers to the specific rational method characterized by a group of individuals who cooperate to make, or refute as the case may be, specific hypotheses related to philosophical enquiry. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Socratic Dialogue’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 12 September 2017, 01:19 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Socratic_dialogue&oldid=800196727> [accessed 31 October 2017] and Wikipedia contributors, ‘Socratic method’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 19 October 2017, 21:38 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Socratic_method&oldid=806126861> [accessed 31 October 2017].

[5] The Republic (Greek: Πολιτεία, Politeia) is a Socratic Dialogue written by Plato around 380 BC concerning the definition of justice and the order and character of the just city-state and the just man. The work’s date has been much debated but is generally accepted to have been authored sometime during the Peloponnesian War which took place between Athens and Sparta at the end of the 5th century BC (circa 431 to 404 BC). The Republic is arguably Plato’s best-known work and has proven to be one of the most intellectually and historically influential works of philosophy and political theory in the history of Western civilization. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Republic_(Plato) for more detail.

[6] The Politics of Aristotle, trans. Benjamin Jowett (London: Colonial Press, 1900).

[7]See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Plato’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 30 October 2016, 18:35 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plato&oldid=746975327> [accessed 30 October 2016] and Wikipedia contributors, ‘Early life of Plato’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 21 October 2016, 15:47 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Early_life_of_Plato&oldid=745516209> [accessed 21 October 2016].

[8] From Plato’s Cratylus, 402a, “Heraclitus says, you know, that all things move and nothing remains still, and he likens the universe to the current of a river, saying that you cannot step twice into the same stream.”. Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 12 translated by Harold N. Fowler. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. From http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0172%3Atext%3DCrat.%3Asection%3D402a. Plato’s affiliation and intellectual influence by Cratylus, and in turn the philosophy of Heraclitus, is referred to by Aristotle, see Aristotle. Metaphysics. Book I .987a from Aristotle. Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vols.17, 18, translated by Hugh Tredennick. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1933, 1989.at http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0052%3Abook%3D1%3Asection%3D987a.

[9] Plato’s theory of forms leverages and synthesizes two key terms that we find throughout Plato’s dialogues, eidôs and idea – εἶδος and ἰδέα respectively. Eidôs stems from the Indo-European root verb “to shine” and is the participle of the verb eidenai. We find it being used for example by Xenophanes to assert that “none have seen the truth of the gods”, oude tis estai eidôs. Eidôs therefore means something along the lines of “visible form” or “shape” but at the same time implies perception, or sight of some kind. It is sometimes translated as “species”, although it is much more appropriately translated as “form”, hence Plato’s theory of forms. Idea is from the Indo-European root verb “to see” and this is the very same root verb, i.e. “to see”, that we find in the Latin vidēre and the Sanskrit vidyā. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘theory of forms‘, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 31 December 2016, 20:27 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Theory_of_Forms&oldid=757634888> [accessed 31 December 2016].

[10] Laws, again believed to be Plato’s last work, is his longest and is the only one that does not portray Socrates in the work at all. In it he explores the nature and source of laws in and of themselves. See Kraut, Richard, “Plato”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2015/entries/plato/ for a review, classification and summary of Plato’s works and philosophy.

[11] The exception to this would be Plato’s Apology which by all accounts is Plato’s attempt to describe the actual events of Socrates trial and Socrates’s actual defense and to a lesser extent the Crito which is Plato’s description of the final conversation between Crito and Socrates concerning justice where Crito attempts to convince Socrates, unsuccessfully, that he should flee his cell and Athens to avoid his impending execution.

[12] It also relevant of course that this method of teaching, the philosophical system of “learning” that Plato is classically given credit for founding, led to the formulation of the first true academic center of learning itself, namely the Academy in Athens which Plato founded circa 387 BCE and persisted for some three centuries after his death, Aristotle of course having studied there for some twenty years before moving on and starting his own school the Lyceum. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platonic_Academy

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!